Clément Chapillon is a French photographer who lives between the south and Paris. After returning to the Gobelins school, he initiated his series Promise me a Land on the link to the land between Israelis and Palestinians which earned him several awards. From this experience, he rebounds with a more personal project on the Mediterranean insularity. Les rochers fauves is taking shape with an exhibition at Polka and a book that should be released at the end of June.

Your serie Les rochers fauves takes place on the Greek island of Amorgos, in the Cyclades. How did you come to know this island, what is your relationship with it? Has the project evolved much since its initial form in 2018?

It is an island that I discovered about twenty years ago, I was young and I wandered from island to island in the Aegean Sea. But I stayed in Amorgos longer and above all, I returned there almost every year as a kind of pilgrimage. At ease there, I felt things that the other islands could not bring me, and human relationships were immediately different, deeper and denser. The place is very remote and quite poor, it is not much a postcard island, this is what has spared it from mass tourism and has preserved its identity and traditions. As I made new friendships with several islanders and after a subject as complicated and heavy as the Israeli-Palestinian territory, I wanted to tell a more poetic and personal story about the link to the land of this small rock lost in the sea.

The isolation felt there profoundly alters our relationship to time, space, the sacred and religion, human and animal relationships, and of course the imagination. So I know what the important ingredients of my story are, but I never know what the series is going to be like when I start it. I’m very intuitive, I let myself be guided by encounters and emotions and as I go along, it’s the lived experience that takes precedence and the pieces of the puzzle gradually fit together.

Your photographs borrow from the documentary style, but the result is a deeply personal and poetic series, can you tell us about this relationship between reality and imagination?

For me, you can’t build a story about insularity without borrowing from the imaginary and poetic register, because when you’re on the island, you’re always facing yourself, plunging into your dreams and deep thoughts. This is precisely what fascinated me about the island, this feeling of being far away, elsewhere, almost in another world. I have walked for hours and passed no one, it feels like walking 2000 years ago, and I was reminded of Henry Miller’s phrase: “the journey in Greece is punctuated by spiritual apparitions”.

“We never arrive on this island by chance, there is a quest for the absolute and sometimes even a desire to hide.”

I remain above all a documentary photographer because I deal with reality, I work in natural light, I also tell a topographical story of the place, but it is by standing on the edge between reality and poetry that I really manage to convey something about this island.

From the title, Les rochers fauves, we feel the splendid color of this rock but also the “predatory” metaphor of the island, an island that haunts us, that possesses us, that obsesses us. A geographical space, but also a mental space, the island is in us even if we are no longer physically there.

The project evokes the duality of the island as both Eden and prison, an isolated land on infinite horizons. Throughout your work, we can feel the impact of the geography on the inhabitants. How would you describe their relationship with the place?

It’s a very paradoxical relationship, everyone loves this island which is almost like an earthly Eden, but at the same time, you want to escape from it all the time. It’s this almost mythological polarity that I’m trying to tell, a duality inherent in us inhabitants. Afterwards, I worked on the native islanders, some of whom have never left the island, but also on the adopted islanders who deliberately came to settle there and who still live there. It is very heavy for some who told me that the island is like a “fly trap”, you can’t leave and you stay stuck to its cliffs and the infinite blue of its sea. Some people experience this insularity better than others, especially those who were used to isolation and who were already living far away from everything in the Pyrenees mountains, for example.

The word isolated means “to take the shape of an island”, if one does not accept the isolation, there is no chance of being able to stay all year round on this tiny territory surrounded by water. Moreover, we often end up there because we say something, we never arrive on this island by chance, there is a quest for the absolute and sometimes even a desire to hide. The island can appear to us as a place of “dereliction”, forgotten by the gods despite the icons everywhere on the walls.

The series takes its name from a passage dedicated to Amorgos in the book La Grèce d’aujourd’hui, a travelogue by the French archaeologist and writer Gaston Deschamps. You used several passages from the book by isolating words, reflecting the ideas of insularity (and ultimately the process of photographic editing). How did you introduce this material and what role does it play in the dynamic with your photographs?

I discovered this book while doing bibliographic research and it is one of the rare historic testimonies about the island. The history of the island is essentially known through oral traditions but very few have been written about. Gaston Deschamp’s book La Grèce d’aujourd’hui is a very rich source on the island in the 19th century. And in this passage of around thirty pages, I discovered a page that for me conveyed all the contradictory feelings about insularity, precisely with this porosity between the real and the imaginary. I wanted to play with this page and use it in my own visual narrative to reflect these specific emotions, a bit like a gateway to the island. I covered the page with white paint, a little in reference to the lime that covers the villages, a paint that becomes a scum on this page, and that leaves words that form a kind of haiku, like a palimpsest that we rewrite on the past.

In your book to be published by Dunes Editions, this principle is reproduced by a system of tracing paper that offers different readings of the same text. How did your collaboration with Dunes begin? What aspects did you work on to transcribe the experience of the series onto paper?

It was a very rich experience, Dunes Editions came up with new ideas, especially for the written part where they imagined a system of tracing paper that covers a page that is given at the beginning of the book. Instead of displaying pages that I had painted over, the reader will be able to discover the “haikus” himself, by placing this page in front of the tracing paper and taking part in the story, by becoming an actor. That was the whole point of Dunes: to create an insular editorial experience. It also takes shape in the long and narrow format of the object itself, a bit like the island, but also in the choice of paper, the cover and the images between them…

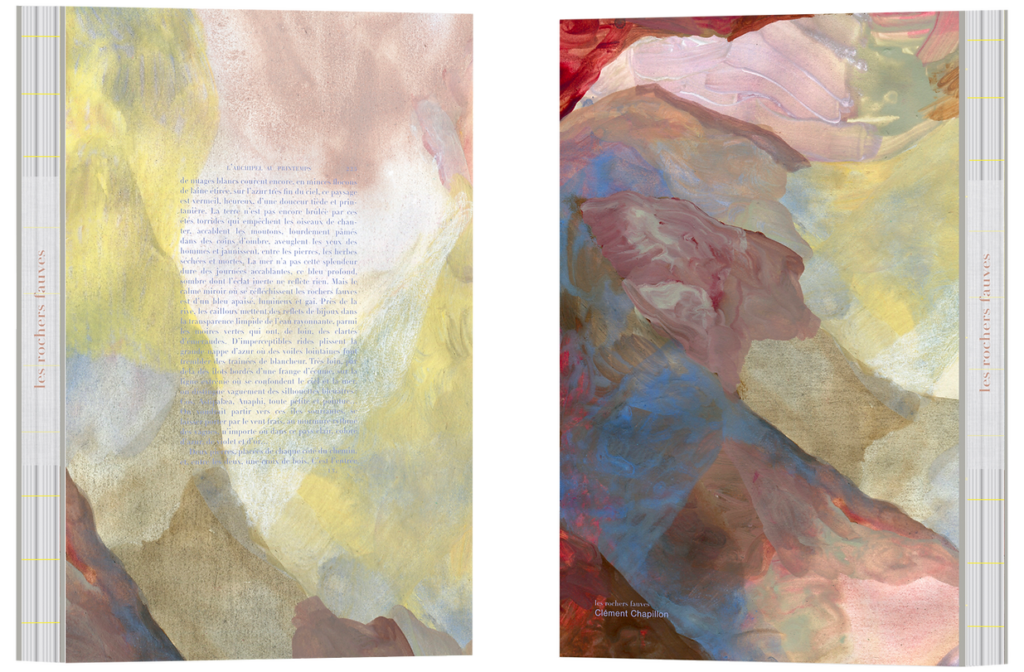

Can you tell us a bit about the collaboration with the artist Nikita Michelsen who made the cover of the book?

It was interesting because it’s something I would never have imagined. I had in mind something more classic, taking one of the photographs and thinking of it as a cover, but Dunes reconsidered this idea by proposing something more original and surprising. To invite an illustrator and painter to transcribe the emotions of my photographs into an original illustration. Nikita immersed herself in my work and proposed several interpretations, and this one convinced us all because it transmitted the imagination, the poetry, the colors and almost the topography of Amorgos. I see the cliffs as my island, but what’s interesting is that everyone can feel something different.

How did you decide on the timing to put the camera down, start editing the series and present it? Are you going back to the island today?

I have made 5 trips and for me, I can’t build the series all at once, it builds up over time. After each trip I develop and scan my negatives and I start to build the story internally. Each time I go back, I go and look for new things, and I realise what I’m missing, the emotions I haven’t managed to capture yet, the characters that are still missing in my series. Afterwards, I never say to myself “that’s it, I have everything I need, I stop”, it’s rather a weariness and a tiredness that pushes me to put the camera down. Of course, I’ll be back next October to offer the book to a lot of people on the island and show them some prints, but I’ll be happy to be able to find the island for myself, without trying to transmit anything. I really think I will always go back, I feel forever connected to this little rock and the people who have settled there.

Les rochers fauves book is available at Dunes Editions, and the photographs can be seen at the Polka Factory, Paris, until 25 June. More to see on Clément Chapillon’s website.