Lens-based artist Shawn Bush grew up in Detroit, MI, a city whose civic history and geographic location have profoundly influenced how he thinks about physical space within American sociopolitical and socioeconomic landscapes. As a result, his photographs and collages are responsive to over-built systems, failing icons, and collapsing mythologies. Bush is the founder of Dais Books and Assistant Professor of Photography at Casper College. His second monograph, Between Gods and Animals was published by Void.

What were the key elements to your photographic education? I don’t just mean photographers and schools—I’m thinking of key life experiences, politics or other forms of art.

I was lucky enough to have many opportunities and life experiences that have shaped my practice. I received a Bachelor of Arts in Photography from Columbia College Chicago and was mentored by Paul D’Amato, which significantly impacted me. After my degree, I worked at Playboy Magazine as the primary studio assistant to the head photographer in Chicago. This experience was amazing and taught me so much about how photography operates to inform identity and mythology, along with how to create in a studio setting. I also worked at DLXSF as a product photographer and junior designer, which unfortunately echoed many aspects of how photography interacts with gender to form hierarchies that reinforce stereotypes. After working in media for six years, I decided to expand my practice and attend Rhode Island School of Design for my Master’s degree, in which Brain Ulrich played a prominent mentorship role. My MFA education was full of politics that continue to shape my practice.

In addition to the images you have produced, the book includes a selection of archive photographs taken by propaganda photographers between 1920-1970. Thanks to inspiring sequencing, the images of the last century are mixed with those of today, without making it too obvious. Ιt’s marvellous when you consider that redefining the context of those photos is like reversing their meaning. Would you like to tell us more about your research on archive imagery and its use in the project?

I would consider the archive, the interest in it, and its use as an extension of the first question in that I moved to rural Wyoming, USA, to teach Photography full time as a collegiate instructor, which was much more of a learning/growing process than I expected. Maybe the most robust growing experience for me yet.

For anyone who knows Wyoming, it prides itself on old Western (American) ideologies rooted in gender stereotypes and Western mythologies of the past. Being here is like a time warp for me, who grew up in Detroit and then lived in cities like Chicago and San Francisco. We do have the luxuries of modern-day capitalist-driven life here. The time warp is more in line with a lack of social progress; it feels like things accomplished in the 1960s and 1970s are still considered radical here. Issues as simple as gender identity, the existence of people who identify as something other than men/women, and the reality that climate change exists are too futuristic for some, including those in power.

When I moved here to teach, I also began to purchase archives and use a large format camera to mimic how those archival images were constructed. It did not take long to see that I could confuse time and authorship of who wrote these rules and who is in control of these systems by simply omitting markers of the present in photographs while shooting with a specific bare bulb flash. When I look back, it provides clarity as to how crazy shit was in the past, though I see that image, that memory of that image, as a mirror of today rather than redefining the meaning of the original. That indeed happens, though, and is the intention of the inclusion of archive images the book/sequence.

Ηave you received any interesting feedback from the male communities across the United States that you had encountered on your shoots when they saw the work you published; or will they probably never see it?

I would estimate that most will not see the work published, though most saw their images in some respect. There were various ways of making portraiture, from intimate friends to strangers I knew for a brief period.

Most portraits were made by contacting people via Craigslist forums and posts I created. Most, or all posts, revolved around the willing participation of men to be photographed in an idealized, mythological manner that relates to contemporary culture. Postings such as Looking to Photograph Men for NFL Trading Cards, Looking to Photograph Bodybuilders, and Looking to Photograph Celebrity Impersonators were some of the posting titles.

I would then meet with the men. Photograph them for hours using a digital camera, constantly showing them their image so they could curate their expression/pose, and then collaborate with what images would be used. They would give me a file number. I would edit the picture and give them a copy. For the NFL trading cards, I would make a physical fake NFL card and send them an edition. I always thought of it as a stand-alone series or series of series. It was not until I looked at the photographs from these shoots in the context of Between Gods and Animals that I understood they could live without data or uniform and represent the same things they did with it.

‘Between Gods and Animals’ is definitely a long term project. Is this a regular feature of your practice? Would you like to share with us how the production has been distributed over the years? Did you try editing the work periodically to see how it was shaping up or what was missing?

It is a long-term project, though I did not explicitly focus on it for the years images were made. It was not until graduate school that I began to look back at older work and focus on making this project only. Having the time to focus on the work and look back during graduate school was extremely important. The title of the book is the title of my thesis. Without that time, I would have never given myself the space to make this work.

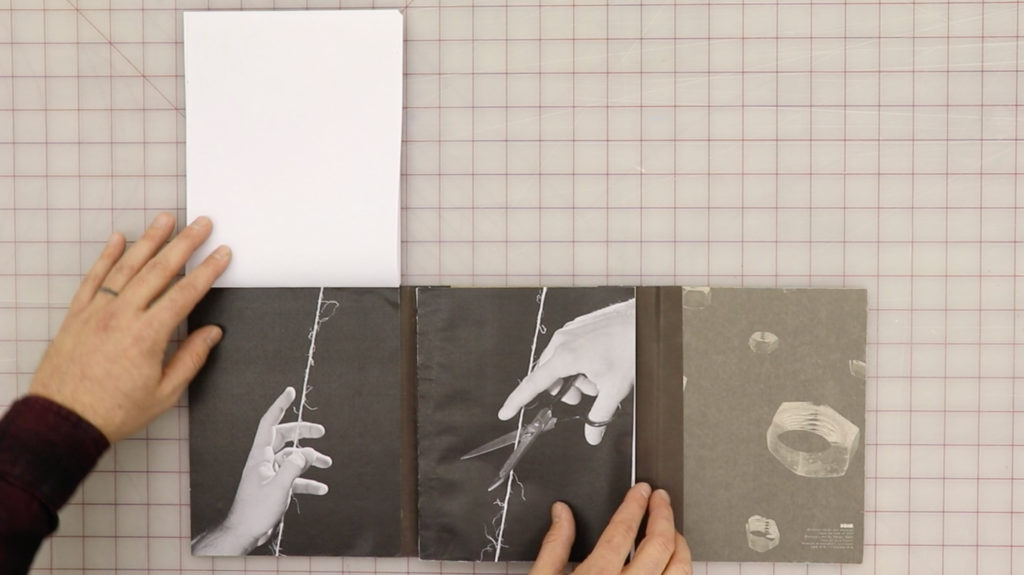

I regularly created book mocks while concentrating on research and image production during my MFA studies. It was not until a few years after my MFA education I began to meld archive images and my own that the book started to take shape. Every photographic project that I create ends up in the book form. Some projects are published, and some are not, though I find the book format to clarify what works, what is missing, and what is close. It also gives an opportunity to begin to think about material and scale as additional communicators.

I genuinely hope to make smaller or shorter-term projects in the future, though I think that whenever those projects manifest in a book format, there will be interplay with additional content or projects. Books can do more than show the most significant hits or best (or only) images in a set. I hope that any book published on my work in the future can give viewers a more extensive understanding of my practice, and I think VOID did that with Between Gods and Animals.

Could you provide us with further insights into the book’s design and your collaboration with publishing house?

We worked together for a few years. I had initially submitted to a collaborative publishing effort that they were doing called VOID x COOP (ironically, I now have a son named Cooper). I applied with just the BGA work from my graduate studies and before. The books had a direction but lacked a punch. We talked about the book, then COVID hit, and we stopped talking briefly. Around this time, I began to shoot only black and white film on a 4×5 camera in response to the archive as mentioned in a previous question.

When COVID hit, it was like an all-access pass to the studio, darkroom, and entire Visual Arts building. I made work 3-4 days a week in the studio and out in the landscape for around six months before we reconnected on the book. At that time, I had begun to juxtapose my new 4×5 black and white work with the archive and my older color images.

Compared to previous book mocks, I could start feeling a punch and shared the new idea(s) with VOID. We discussed many things about what I deemed successful through my several mocks, along with books that I enjoyed because of design/material/production choices and how that can come together as a VOID designed book. I gave them 100% access to the new black and white work, much of which is now included in my Angle of Draw series, and they took it from there.

The installation of the project ‘Angle of Draw’ that is currently on view at Candela Gallery

Being aware that you’re entrenched in the publishing industry as the founder of Dais Books, does your grasp of the subject impose a greater sense of meticulousness upon your own book’s creation, or does it grant you a sense of liberation?

I am certainly aware of production errors and successes and how those could be avoided. VOID does excellent work. I own several titles and never questioned the quality of production. They know what they are doing and work with a printer that invests similar love and dedication into producing photobooks. For me, that was more than enough to feel liberated or comfortable.

Could you share a documentation photo of this project displayed at a recent festival or gallery exhibition that represents the project? Within the realm of photography, some artists primarily publish their work in books, while others lean towards showcasing it in exhibitions. It’s evident that you appreciate both avenues. How do you experience the sensation of witnessing your work being presented in diverse environments?”

I cannot share anything because I never considered this work a gallery exhibition. I always thought of this work as a book. Partially so because there are so many formats and cameras used (35mm, 120mm, 4×5, 8×10, digital, medium format digital), though more so because I didn’t want to make an exhibition that looks beautiful or glorifies white maleness.

The closest I have is from my MFA exhibition, which focused on the same themes, though visually manifested differently. The pieces in that show are all, in a sense, collages. There are two layers of inkjet prints, with the top layer being the same images in different densities printed on a perforated vinyl used for advertising. Underneath is a series of portraits of men. The men also appear in a two-channel video playing on a deconstructed television on a stack of wooden shipping pallets. This is titled F2D on my website.

During my education, I worked with those men for two years, learning much about sociopolitical and socioeconomic landscapes intertwined with social hierarchies through making videos and images of them flying model airplanes in a combat-like fashion.

What is the most significant contrast in your perception of photography today, in comparison to your initial days at university or when you took your first shots?

The most significant change, in my opinion, at least in the United States, is accountability and impetus. Why was the work done, and who made it seem to matter just as much, or in many instances more than the work itself. The days of white men documenting cultures they do not belong to for their own interest or gain are over. That being said, those established as essential figures within (contemporary) photography will always have their fans and sustain.

I am getting increasingly interested in the history of photography/media and those that reflect on that or play with the physicality of the medium in imaginative ways. Any work that is genuine and visually inventive also attracts me.

More on his website