Rita Puig-Serra Costa is a Barcelona-based photographer. With a background in Humanities and an MA in Comparative Literature, she later studied Graphic Design and Photography. Closely related to literature, Costa’s work revolves around the concept of identity. Her investigations also explore the essence of human relationships, and the influence that love, death, luck or memories have on the construction of ourselves. Today’s discussion will revolve around “Anatomy of an Oyster,” a project published by Witty Books.

In this book, as in your earlier ‘Where Mimosa Bloom’, you make inventive use of the family archive. How do you navigate the process of choosing images from your personal family archive and transforming them into representations of universal significance?

When I develop a project I start from the particular -that which worries me, makes me uncomfortable or hurts me- to find answers in the more universal. Somehow, I try to find the connections between my personal experience and the experience of others. Thus, in this search for answers, which is where the research, the documentation prior to the project, takes place, I travel in a loop from inside to outside. That is, from my intimacy to the intimacy of others, to the theory and the concept. This allows me to move further and further away in order to see the treated subject from different perspectives, from different points of view and, in sharing it and looking outside, to relate it to the political and social structure.

When I finally have a clear picture of the whole, a bird’s eye view, is when I can start shooting the images, previously looking for the symbology that will help me to express what I want to tell. And this is where the archival image comes in: the use of archival material -both images and found documents, writings, illustrations- helps me to frame in a concrete way, in a particular scenario, a family and specific dates, my own, the theme I’m talking about. It is a way to give it a name and surnames, to show a trace, to give it an identity. And that allows this journey from the inside to the outside, from the personal to the universal.

In the specific case of Anatomy of an Oyster, the archive also functions as proof, as a trace, as a verification of what happened.It’s undeniably a courageous choice to address such a deeply personal subject. It appears to be a step toward confronting, sharing, and ultimately releasing these emotions to others. It’s a mix of vulnerability and audacity that artists have frequently demonstrated throughout history.

Could you provide some insight into how the initial idea for this project originated? From my perspective, ‘Where Mimosa Bloom’ serves almost as a prequel to your current work, indicating your enduring fascination with this specific thematic focus.

The elaboration of this project has been a long, very long process. More than six years have passed since I started it until the publication of the book. And during this time I have had many doubts about whether to continue or not. The subject of the family has always interested me. And if I review the projects I’ve done so far, it has always been present: the first project I did when I was studying photography was about my grandmother, Santa Memòria; then the death of my mother, in Where Mimosa Bloom; the breakup of a couple in Good Luck with the Future (which I did with Dani Pujalte), and now the issue of abuse within the family. And yes, as you say, Where Mimosa Bloom works almost as a prequel to Anatomy of an Oyster. In fact, in Anatomy of an Oyster, I continue the conversation I started with my mother in Where Mimosa Bloom. And I continue it to tell her what I didn’t dare to do before. I think somehow I needed to open this channel of communication – with my mother, as I did with Where Mimosa Bloom-, so that I could verbalize it later.

What potential interactions exist between photography and text? Many photographers note that this combination is among the most challenging endeavors they’ve undertaken. As I pose this question, I’m considering your incorporation of text within your own work.

The use of text in my projects works in a similar way to the use of the archive photo mentioned above. That is to say, the text helps me to concretize, to bring down the more symbolic and conceptual part of the project to the more earthly. It is a way of illustrating what is being told in the images. And precisely in this project, I think the text makes all the sense in the world, since the project is about what we do not dare to tell, what we are not able to bring out from inside, to verbalize, because there are moments when it seems to us that we have no voice. And the struggle here has been to go deep inside to dare to bring out what was hidden in the darkness, the pearl. To tell it to me, to tell it to the world and, above all, to tell it to my mother. Through images, yes, but also through words. And that is why the book begins with John Bowlby’s quote: “What cannot be communicated to the mother, cannot be communicated to the self” and ends with a scream.

In your broader photographic body of work, portraits seem to be a prevalent feature. However, in contrast, this book showcases a more restrained approach, favoring still life and close-up shots. Could you elaborate on the factors that led you to choose this particular artistic direction?

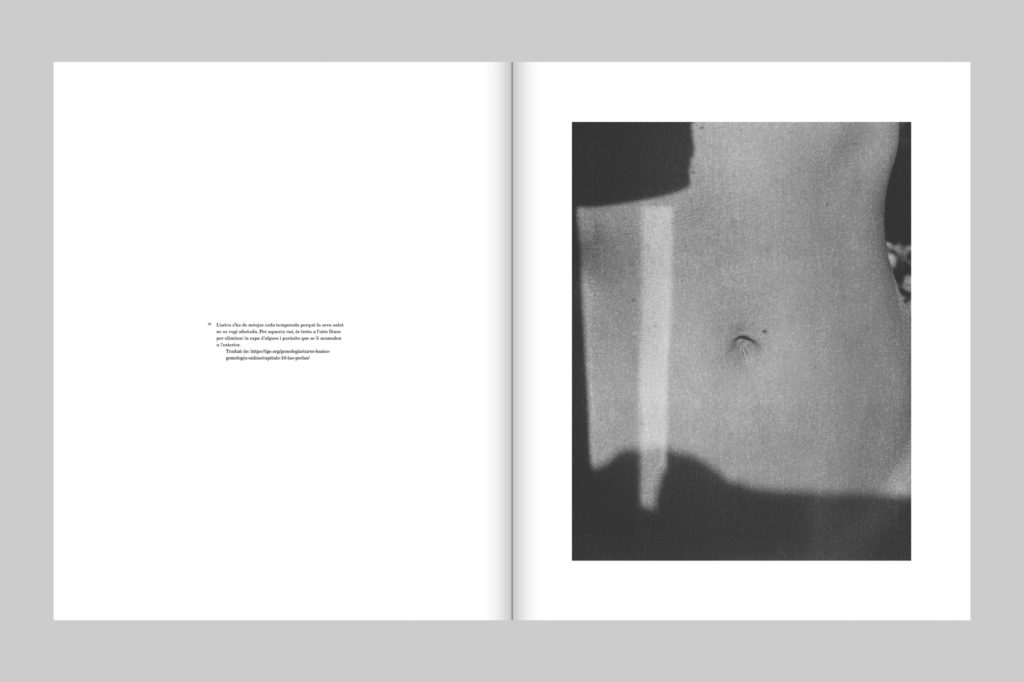

Both at a formal and conceptual level, the close-up is fundamental in the project. The exercise of introspection that I have carried out to be able to bring out what I had inside has gone hand in hand with an exercise of maximum approach at a formal level. That is, I wanted to look as closely as possible at the pearl. To photograph it with a macro, to appreciate its tiny forms, its details, its lights and shadows. To travel as close as possible. And to understand that something that a priori can look very small, can feel like an enormous weight. For me, macro photography (which I discovered with this project) has something of a ritual, almost a meditation: you have to control a lot that nothing moves, your body, your breathing. It requires a lot of concentration and being very present. Which is the same process that I have done at a therapeutic level.

I have also used the close-up with the archive photos of the eyes: to search in the family archive for images of the person who abused me and to get as close as possible, in order to transmit the violence that this look has generated in me. In an exercise of total catharsis, I also made close-ups of different parts of her body: her hands, her fingers, her gaze now. Like a detective in search of evidence and details, in this exercise of memory, the use of the macro has been key.

The project ‘Anatomy of an Oyster’ is undoubtedly a long-term one. Is this a recurring aspect of your creative process? Could you provide further details about the evolution of the project’s production throughout the years?

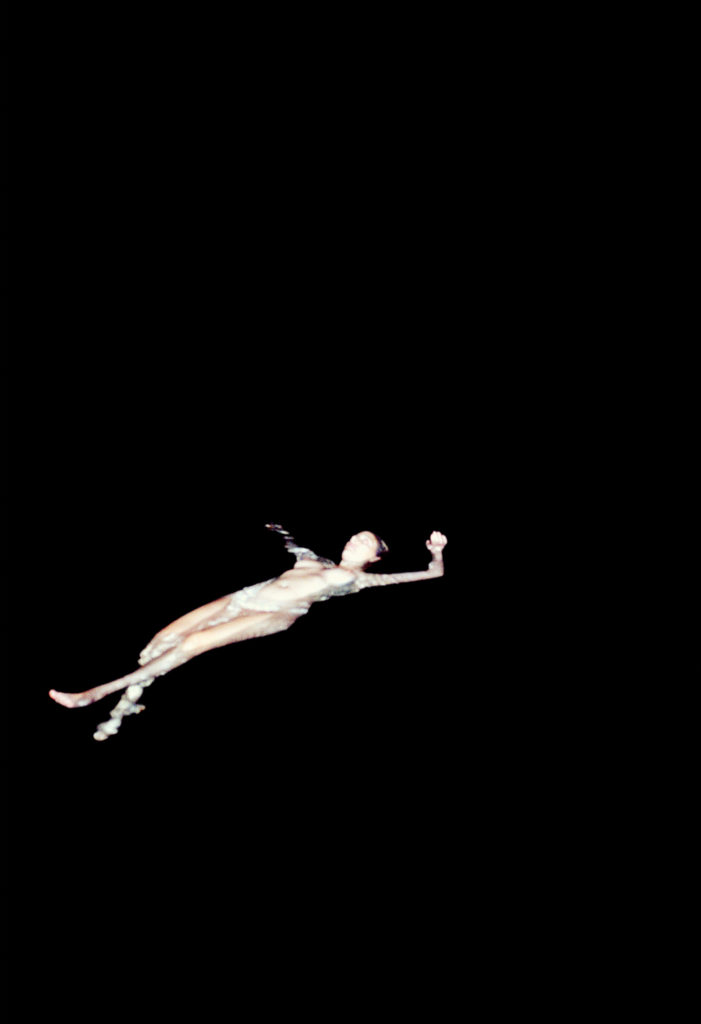

As we mentioned above, the project took a long time to develop. It felt like a long-distance race in which I had to be very cautious because I have been advancing at the project level at the same time that I have been advancing in a more therapeutic sense. The doubts about whether to continue with the project or not have been repeated in different phases and stages of the work. And even around me I have had family and friends who have recommended me not to do it. It has been a great challenge to go ahead and finish it. In the end, thinking about how projects, books, films that deal with issues that touch me have helped me is what has encouraged me to go ahead and try to put this small grain of sand in what, fortunately, is becoming a growing collective consciousness in relation to the subject. Before I started shooting, there was a very long phase of documentation: both at a more theoretical and conceptual level – bibliography on the subject (both fiction and essays), conferences, films and documentaries – and at the level of the family archive – searching and searching for clues, evidence and details, among family albums and my letters and diaries from when I was a child. Then, once I was clear about the use of the pearl as a symbol, came the pictures of oysters and pearls. I traveled to Indonesia and there I could visit a pearl farm where they explained me how the whole process of pearl creation works, at the same time I was taking pictures. Then followed all the rest of the images: going back to the house where everything had happened and taking the photos, more tests; making the close-ups of the baroque pearls; the close-ups of the hands and eyes of the person who abused me; the images of the sea; recreating a letter that I wrote to my best friend when everything was happening and that we burned in a park… And finally came the texts.

Could you delve deeper into the specifics of the book’s design collaboration with Ana Domínguez, as well as your partnership with the publishing house Witty Books? Who initiated the partnership in each of these instances?

I have known Ana Domínguez for years because we both worked at Terranova publishing house, she as a designer did almost all the books of the publishing house and I was in charge of the editing part. We became close friends there. I was very clear from the beginning that I wanted her to design the book. From the beginning I wanted a woman to do the book, and then Ana’s intelligence, sensitivity, elegance, sobriety and taste seemed to me super suitable for the idea of the book I had in mind. We both thought from the beginning that it would be interesting for the book as an object to be related to the oyster and the pearl, but we didn’t want it to be too obvious. With her, Ana Habash, who works in her studio, Anna Manubens, who is a curator, and Tommaso Parrillo de Witty, we worked on the edition of the project. I think the idea of using a black folded dust jacket that hides a baroque pearl on the back that becomes gigantic when unfolded is super successful. I also love that the baroque pearls with black background occupy the central place of the book, as the pearl occupies the center of the oyster. And that one has to go through the whole exercise, uncertain and painful, of the pearl work, in parallel to my journey into the past to try to assimilate, to get there.

I met Tommaso Parrillo in 2022 in Arles, at the presentation of the book Praise the Lord by my friend Dani Pujalte. I have loved Witty Books for a long time and it seems to me that the books he publishes are very much in line with Anatomy of an Oyster. There I told him about the project I was developing. Just as with other projects I had not felt this need, with Anatomy of an Oyster I saw the need for an editor to help me in the final selection of images and in the sequencing. Working with him has been super easy, fluid and enriching.

Could you provide a documentation photo from a recent festival or gallery exhibition that showcases this project? In the realm of photography, certain artists predominantly feature their work in books, while others gravitate toward displaying it in exhibitions. It’s clear that you value both these avenues. How do you feel when you see your work presented in various and distinct settings?

I always think of projects in their final format as a book. In fact, for me the work is the book. Once the book is done and published, I can think about its arrangement on the wall. And right now I’m working on it. I love that the project can take on new forms, and I find it very exciting to give it a new life on the wall, but the base is always the book.

What were the key elements to your photographic education? I don’t just mean photographers and schools—I’m thinking of key life experiences, politics or other forms of art.

Literature as well as books as objects have always fascinated me. I studied literature and then did a master’s degree in comparative literature. And I spent many years working in the publishing world, until at 30, when I made Where Mimosa Bloom, I decided to take a professional turn and try photography. It was after my mother’s death that I felt the need to express myself visually: I am an only child and I had all her objects at home. And I thought it might be interesting to make a sort of catalog with images of all these objects that one day would disappear from my life. That’s how Where Mimosa Bloom started, and that’s how I began to feel this need to communicate through images. I think that both my mother’s death and my literary studies have been key in my development as a photographer.

Would you like to share with us some of your favourite artists (from photography, music, film, etc.) that you are currently following?

Right now I’m listening to Durutti Column, reading Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir’s “Animal Life” which I highly recommend and hooked on Jacques Audiard’s movies.

More on her website