Katerina Moschou is a visual artist who lives and works in Athens. She moves multidimensionally between sculpture and photography, with printmaking and painting constituting the stable components of her creative process. Her works share a meticulous observation of both human-made and natural environments, capturing the intricate web of relationships that unfolds within them. Her first photobook “How to drive” co published with Zoetrope Athens received a support grant from Polycopies & Co (Paris 2022)

Asking various people who have seen your book about what they get from it, I heard a variety of things from which some repetitions stood out: the presence of a woman behind the wheel breaks the stupid patriarchal stereotypes that associate men with cars, the tribute to the charm of driving against the routine of everyday life, and even references to the kinds of photography based on roadtrips-only here we can hardly see what’s outside the glass. Then there’s the suggestive relationship with your father (a car mechanic) hinted at at the beginning of the work. Really, what made you start this intriguing project?

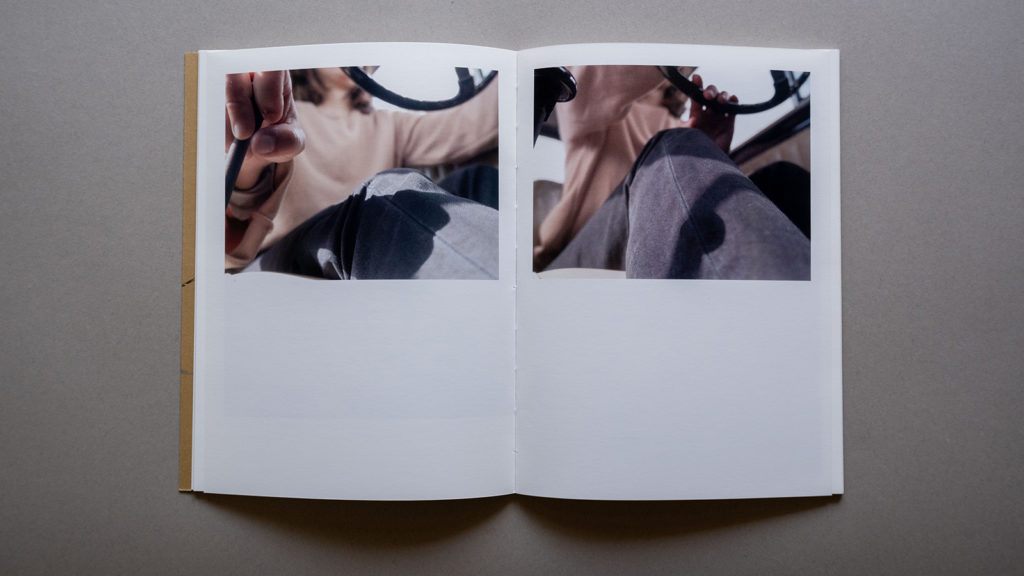

The starting point of my artistic process is deeply rooted in spaces intertwined with the notion of non-inclusion – embracing whatever is excluded or marginalized. In the early days of ‘How to drive’, I’d find myself daily in my father’s car workshop. It presented itself as a perfectly enclosed sanctuary, a refuge where I could spend countless hours photographing objects with a particular personal connection. These items have consistently framed my visits there over time, creating a backdrop that, despite its continual transformations, retained familiar textures. They remained visible, yet never tactile. It feels like there is a protective barrier that unwittingly hindered me from establishing a substantial connection. In an effort to create a routine within the car workshop, I endeavored to comprehend how I, as a woman, could forge connections in this environment. Through touch I was becoming, in a way ,one with machines and materials that, since childhood, had seemed somewhat unapproachable. Another catalyst for delving into car interiors was Ursula L. Guin’s book ‘ The Carrier Bag’. In this book, Le Guin suggests an alternative reading of history, a wholly different concept of what’s worth narrating. I had been carrying this subversive idea and while shooting cars it suddenly sparked.

Looking at the sequencing of the book at several periods, it is almost like watching a stop motion that allows us to dwell with time comfort on images that in everyday life we pass by in a hurry, since for most people one would say that the act of driving is done mechanically. Could you reveal a few facts about the much-discussed step in contemporary photographic production, the one of sequencing? On what thoughts did you start out with in putting the images side by side?

Exactly, there is a sequence of gestures that unfold almost unconsciously, never captured as we drive. The body has its own language and vitality that we often forget, overlooking its dynamics. This project evolved through a daily ritual of driving, more or less like a repeated performance in three different cars, in small enclosed spaces. In this sense it’s no wonder how the body itself influenced the sequencing. “How to drive” unfolds like a rhythmic dance between body and the surroundings, the body and the car parts. It’s all about keeping this somewhat cinematic movement alive that resembles a ceremony. Undoubtedly ,forms, colors and an attention to the subtle movements of bodies contribute to the sequencing.

With a fine arts education, you use photography, painting, sculpture and installation as your medium. Once you have an idea how do you decide which tool to use? Is it something that arises organically or do you prefer to decide at the pre-production phase?

In the beginning, I let the first idea guide me, allowing this lasting impression to take shape in my mind. Often these ideas are closely intertwined with the sense of materiality. As I delve further, a crucial factor for me becomes communication within the artwork – understanding what and why I want to create. This interplay directs me as I both subtract and add elements, all while considering the chosen medium.

The creation of this photobook prompted an exploration of both the subject matter and photography as a primary medium, without direct communication with other art forms. This experience unfolded as a parallel process of appropriation and exploration – an attempt to intimately connect with the medium and discover a new visual language within it. It’s a way to narrate the book’s story and at the same time challenge myself with the medium of photography.

Do you see any significant differences between contemporary art photography and the corresponding actions of visual artists?Approaching art as a unified field allows me to think without imposing limits on the creative process and giving myself the freedom to engage with various art forms. This approach helps me avoid rigid groundwork, fostering observation and exploration. Each encounter with a different artistic medium serves often as a fresh approach, considering various ideas, narratives, materiality etc, as starting points. I try to focus on the essence of the process by exploiting the medium.

Nevertheless, I acknowledge the differences, and it’s particularly intriguing to choose the most suitable way to enhance certain qualities. I observe how certain aspects from one medium can influence and function during the process when working with another. In every circumstance, these differences contribute to transforming a broader artistic language if we are open to adopting them.

For the development and publication of ‘How to Drive’ you collaborated with a new space in Athens, Zoetrope. Which aspect of the process of creating the photobook did you find most enjoyable and which was the most exhausting?

This book took shape during the workshop ‘Time to Blossom’ at ZOETROPE ATHENS and our collaboration later expanded to co-publish it. Working with Yorgos Yatromanolakis (co-founder of ZOETROPE ATHENS), has been a smooth process all the way, marked by trust. It definitely operated as a kind of learning platform for me, having to deal with a whole new world. Yorgos allowed for ample space and took interest in the essence of each choice. Thus, on both sides, every proposed change in editing/design served a specific purpose for the book.

I believe the most challenging aspect of this process was dealing with issues beyond our complete control that arose and required resolution. It was a gratifying experience to navigate through these challenges together.

Additionally, there was a moment of self-doubt just a few days before the book went to print, where you question all the choices and work you’ve put in for so long. However, I believe this is a part of the game.

Can you give us some info about how Photography is perceived as a medium of art in your homeland? What do you appreciate the most?

It’s great that I observe the emergence of intriguing photobooks and more broadly, engaging photographic works that bring a fresh perspective. This is particularly inspiring for me, given the challenges artists face in Greece.

How is driving in Athens?

To put it mildly it’s sheer madness with a strong sexist accent. However, I enjoy driving late at night in Athens; everything is somehow calmer.

What is the most significant contrast in your perception of art today, in comparison to your initial days at university or when you took your first shots?

One aspect that stands out, particularly in general for artists in our time, is the difficulty of fully immersing oneself in a project, unlike the university days. I mean, we often find ourselves juggling multiple projects in the art field to meet financial demands, and this inevitably influences both the production time and our reflective process. It’s a condition of our era that undeniably shapes and characterizes the art scene.

I also try to see ‘completed’ work not just as a step but as a crucial phase in my way as a visual artist. These perspectives, refined over the years, propels me forward recognizing the outcome as a juncture that leads to every new creation.

More on her website