Julia Albrecht is a German born fine art photographer whose work is based on a linking examination of sociological and gender-scientific research as well as an intensive preoccupation with personal experiences. It constantly draws from a profound curiosity for humanitarian issues and cultural phenomenons.

Could you speak first about your early life to set the scene? Where did you grow up and how did that environment shape you?

I have to admit that I was never a fan of this question because I don’t know how to define it in a simple sentence. However, it’s my time to shine as you don’t want me to answer in a simple sentence. I am convinced that my background and the environment I grew up with are important factors of my artistic development. Underneath the surface of the exterior are essential issues that touch every aspect of our lives. They influence our perception in every possible way.

From an early age, my family had been on the move constantly. The real reason for this, I have only learned many years later. For some topics, you are too young to understand them properly. After a specific time, the façade of the perfect life begins to crumble, and the crumbling plaster reveals the broken foundation. Something like this affects all of us even if we don’t want to admit it, or they are just better at hiding them. You don’t talk about bad things because they destroy the happy family atmosphere. This turmoil at a time when I should find myself as a human being was a melancholy experience. I never really felt that any of these places belong to me. Sure, there is the small village of 300 people in the middle of Germany where my parents still live, but I feel ripped out of too many moments in my life that I can’t say I belong there. It seems like I erased them with every hard drive I destroyed. Many things lie hidden in my subconscious that come up now and then.

There is a trigger in everyday life matters like my father’s car scrapyard and his oily hands. My mother, who sacrificed her job to devote all her time to the family. A simple working-class family cursed by the past, which balanced the struggle from day to day. The riding stable and horses, the nature that always surrounded us, as well as the isolation that went with it. Starting from the small corner to more significant local issues. Memories that smell of gasoline.

So I’m trying to put the pieces of the puzzle back together. Guided by my feelings, instincts, and empathy for others’ feelings, I reflect on them constantly until I understand the origin – the curse and blessing of every overthinker.

What were the key elements to your photographic education? I don’t just mean photographers-schools—I’m thinking of key life experiences or other forms of art

There are a few essential episodes in my artistic education that brought me to the place where I am now. One of the first was most likely my semester abroad in Boston, where I produced the series “Destiny of a white horse”. This series has changed so much from my portfolio that I can no longer identify with previous works anymore.

Metaphorically, I have started to transform the first effects of my depression with this work. To not lose myself in my empty thoughts, I buried myself in my workflow – The same story about the projects that followed from this. At some point, I realised that dealing with art meant dealing with more important life issues. My life experiences, the feelings and emotions associated with them lead to various themes in my photographic series. Perhaps photography was a way to convert my childhood and memories and address social and philosophical issues.

Stepping out of this hole again and loosening the shackles I put on myself was helped by the artist residency Studio Vortex under Antoine d’Agata. He has a fascinating way of reading people and always asks for the deeper reason behind everything. Those two weeks were probably the most intense of my career so far, making me question my previous projects and find out the core of it all. A quote that I always like to hit on as a reference is Goethe’s Faust: “This was the poodle’s essence then!

Concerning my master’s thesis, I started to see my depression as a political issue. In my opinion, art is not there to please society, but also to advance things and essential matters. I can use it to link research and present it so that it is easier to digest for the viewer who might never have bothered with the scientific background. My studies at Bauhaus-Universität laid the foundation for this, which I can explore further at the Royal College of Art. In general, I think the aspect of art and science is something I would like to continue to pursue in my academic career.

In the ‘Diagnosed with phantom pain’, as well as in your previous works, you are interfering with the unequal place of women in modern society. Your practice includes apt use of many symbols and parallels. Would you like to refer to some of them?

The term woman does not only refer to biological terms; it instead describes a role into which an individual is forced. Hardly hatched from the cocoon, women are confronted with many pressures throughout their lives, including physical and psychological ones. Biologically, becoming a woman is not difficult. On the other hand, learning social roles can be complicated because these characteristics are not innate but have to be discovered. It is a cultural code inscribed in our behaviour, actions, health, and illnesses in our bodies.

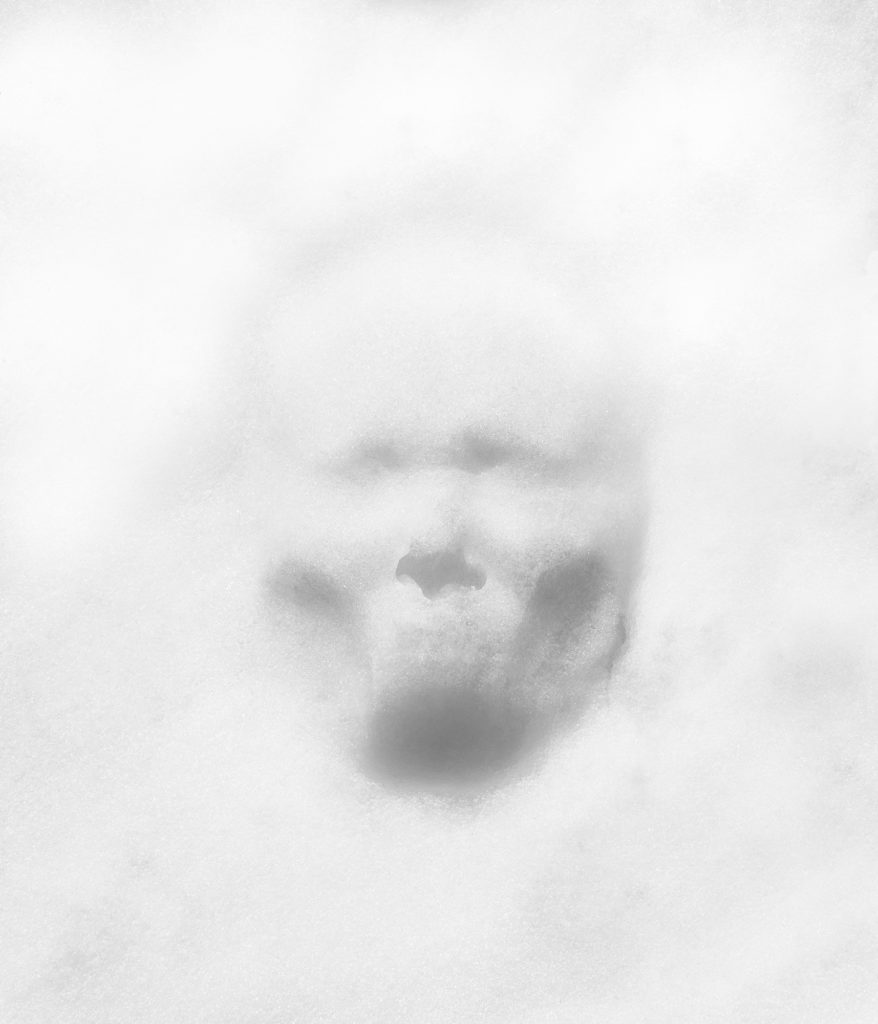

Depression is a mental disorder that affects women more often than men. Gender-specific personality traits, in particular, are considered to trigger depressive disorders in women. For me, depression reflects an emotional crux related to my family or myself at different stages of life. I surf the ironing board of paradox. It is not just about an analysis of female depression. It’s also about presenting an individual perspective and exploring what it can mean to be a woman – or rather, how I feel about being depressed as a woman.

Instead of rethinking, we groom ourselves into the roles we are supposed to play in the theatre of life, trimming off every branch that shows just a single piece of diversity; what is left behind is the seemingly marrowless crystal tree. I no longer want to carry it around like a dull, draught horse. For this reason, I began to study my behaviour as a woman in western society to find my solution against drowning.

If we think of Freud’s theory of penis envy, it is women who are taught to feel incomplete without the interaction of a partner. As if marriage is the only way to get hold of such a phallic trophy. I find the tradition of the bride being walked down the aisle by her father a little oppressive. She is passed from one man to another as if she were a piece of property. It also often happens quite unconsciously that after marriage, women fall into old role patterns and give themselves over to the more domestic duties more often than their partner. As if there was a cleaning gene. The burning stove reflects this behaviour, which can lead to frustration after a while. The hot plates of the oven begin to burn the tawdry veil, and what remains is only ashes and vermiform pieces of the prophesied promised land.

No country has yet achieved gender equality. It is not about fixing one gender or the other. We need to work together to achieve a better and stronger togetherness, just like the snails, which as hermaphrodites, only decide on their gender when they become sexually active. Before and after that it’s irrelevant. Sometimes, when you look deep, you don’t recognise the language, but it’s there, so it has to be heard, and sometimes the language is called depression.

The title of the project may imply the therapeutic quality of photographing. Why and how can the medium of photography be a therapeutic instrument?

Photography acts like a marker that shows me where I have been and how far I have come. It helps me understand how I see things. That’s how I organise my thoughts. In the beginning, they are often perplexed, but after a while, they form a thread that leads me to the quintessence of my dilemma. My projects emerge mainly through the process of therapy and give me a safe space to break out of my silence when I have lost my voice. Only through processing can gaping wounds can be healed.

It is often the case that I fail in interpreting my feelings at first. I admit this openly. My camera and my notebooks are a mouthpiece that helps me in these blurred times. To speak out and to translate my innermost feelings. I guide my thoughts, so I don’t squash any sparks – A way of control to regain my ability to think.

This value of physical and artistic thinking is only a discovery because the knowledge on which this work is based comes mainly from experiences and fears. It reflects a path of healing and understanding. Another benefit of this is that it avoids demographic science and allows my artistic engagement to transcend to a personal level. In turn, the observer can better empathise.

We have no control over what happens to us in life, but we can learn from it.

“Art is not there to please society, but also to advance things and essential matters. I can use it to link research and present it so that it is easier to digest for the viewer who might never have bothered with the scientific background.”

Ιn some of your recent exhibitions I have noticed the extensive use of cobblestones in the installations. Can you tell us how this decision emerged?

Where I come from and what has influenced me is an essential factor in my artistic progress. They are connected to the individual projects and, of course, must not be missing from the installation of the exhibition. My father’s workshop is on an old factory site that has often been a setting in many of my dreams and memories. The cobblestones and the structural steel are elements from the industry that I use in my work, like a cold floor of truth. – Fragments that have anchored themselves in my subconscious. Together with the fine art prints, they form a contrast. It is a break that underlines the uneasiness of the subject matter.

In principle, I find the play with ruffles and fine materials very interesting. Be it a high-quality baryta print stapled to the wall or a photo on the finest silk hanging from steel chains. In ‘Diagnosed with Phantompain’, the individual images were presented in self-made shadow gap frames made of construction steel, which frame the prints like cold bars. They leave enough space to breathe freely but not enough to be free.

Some photographers prefer photobooks, while others prepare exhibitions for presenting their work. Taking into consideration your artistic activity, you probably belong to the second category. Where would you place yourself, and why would you prefer this kind of presentation?

What are the possible dynamics between photography and text – how and when do they enhance each other?

I have found writing to be a contemporary method of combining scientific theory with my way of working out the knowledge I have gained. Everyday life, depression and familiar feelings are not immediately associated with a comprehensive diagnosis or explanatory framework. This includes a practice of writing and artistic work that was guided by emotions during my depression. These personal streams of thought are mixed with historical and scientific studies.

Looking back, ‘Diagnosed with Phantompain’ helped me form a vision for myself and develop authenticity. I have succeeded in finding my path of artistic practice and linking it with scientific research. This has created a hybrid that is nourished by other scientific fields. It offers the possibility of exploring complex areas, letting them speak through artistic design, and sensitising a broader mass for these topics far outside the usual experts.

For me, photography and text form a symbiosis that is beneficial to both. One supports the other and vice versa. One brings autonomy, and the other puts its finger on the wound. They let go of each other and look for each other again.

Since my workflow is much connected to my research, the two go hand in hand. In the meantime, I have also found a lot of fun in writing and see it as my second medium besides photography. So much so that I could imagine writing a book about the themes I focus on in my work, which is, of course, linked to the photographic work.

This is ironic because I didn’t do well at school and honestly hated reading. It’s interesting how everything changes throughout a lifetime and how you suddenly start to burn for something that at first felt like vinegar on your tongue.

What are your next steps?

After each project, questions remain unanswered that cannot be solved within the scope of the work. More projects will come, and I will dive deeper into the matter. What does freedom look like? Does freedom have to exist? I see it as my task to draw attention to social, societal and political debates and to do my part to solve them. I am not a psychologist, but I can use psychological studies for myself to turn them into something bigger with my own experiences. I see this as my responsibility for the future.

Caroline Criado-Perez wrote in her book Invisible Women: “The lack of meritocracy in academia is a problem that should concern all of us if we care about the quality of research that comes out of the academy, because studies show that female academics are more likely than men to challenge maledefault analysis in their work.” This quote inspires me and I am thinking about doing a doctoral degree programme next to find more and more a way to combine my artistic approach with scientific facts.

Stay fragile, be fragile, in connection with the world.

More on her website