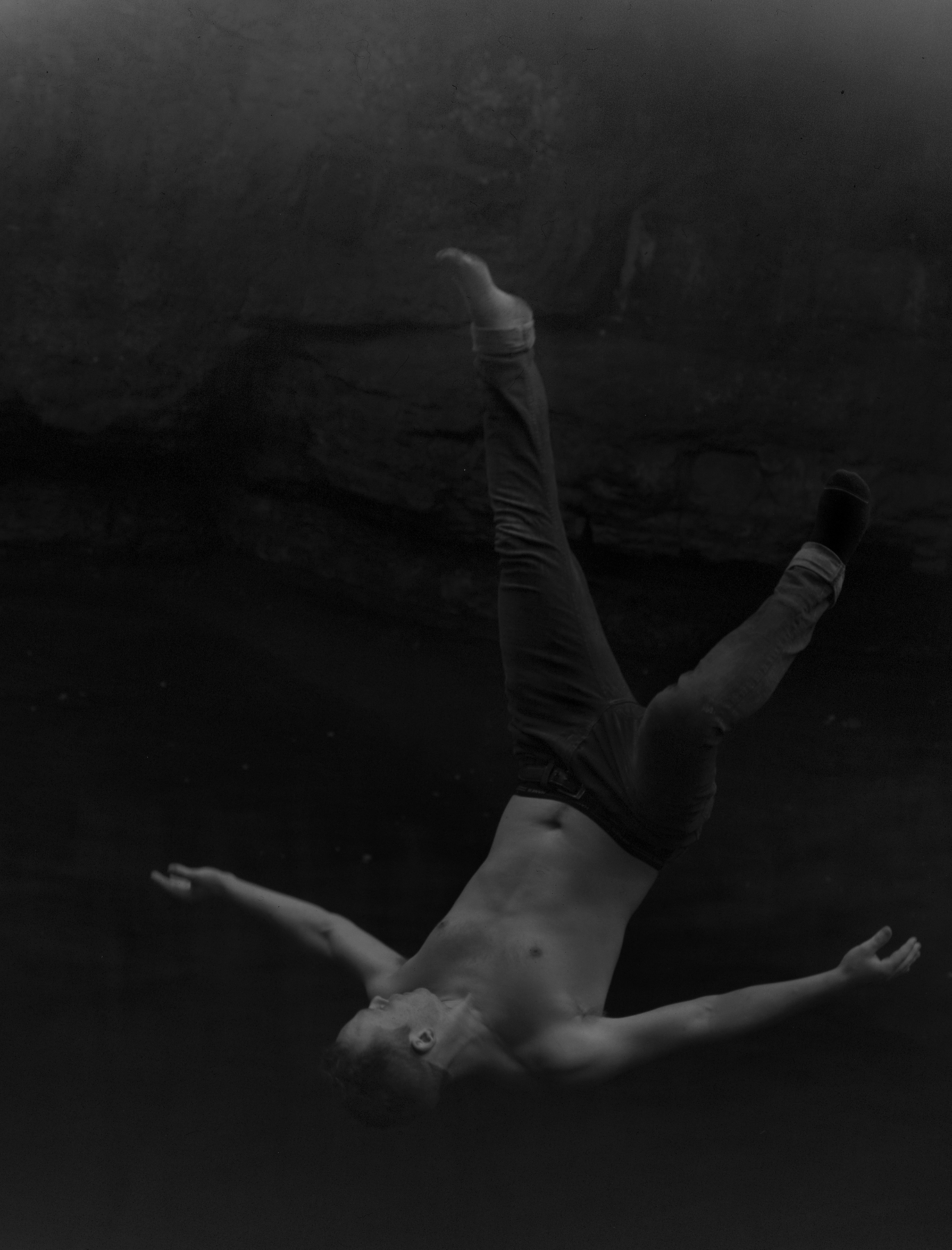

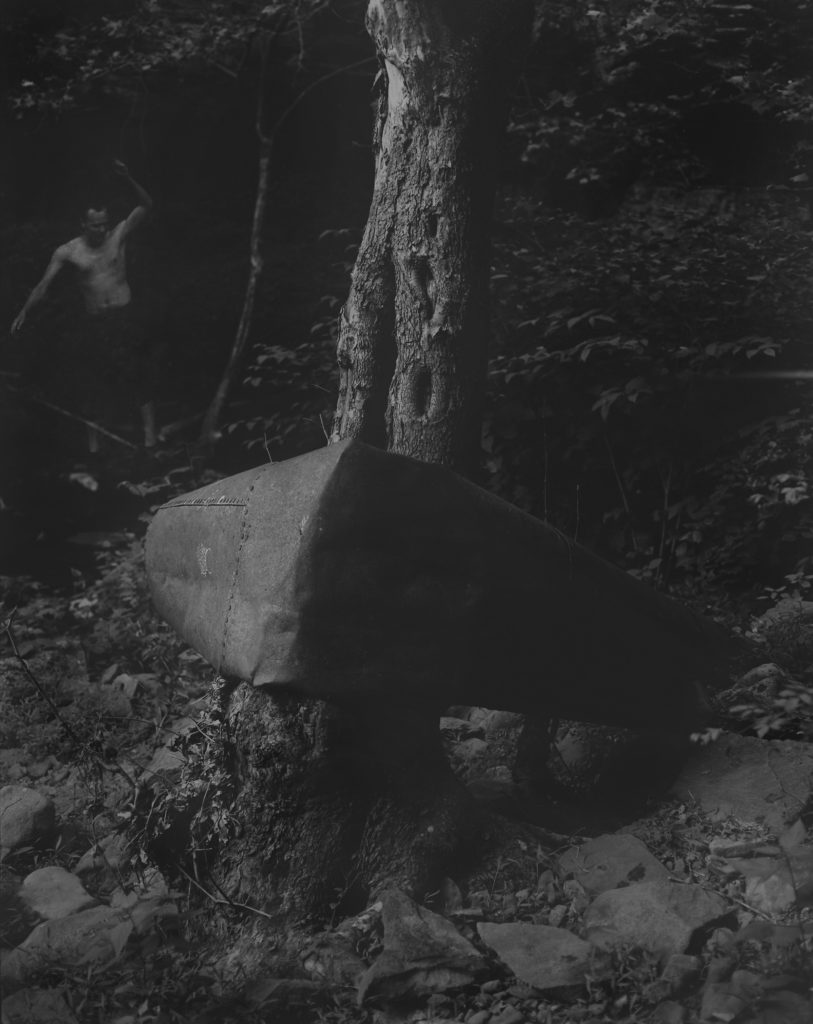

Raymond Meeks lives and works in the Hudson Valley, New York. He gains inspiration by book narrative and collaboration with writers of poetry and short fiction and the merging of image and text. Halfstory Halflife, his recent body of work, is a visual biography of the post-teen age, in a specific time of the year, that leads from blizzards on unknown paths to leaps into darkness.

Leafing through the book I cοuld smell the water, the grass, the stones, the loud noises of the local youth. It’s like it’s like being one of them, you don’t seem to be observing this life candidly at all. Ηow did you make them appear this intimate around you and your camera?

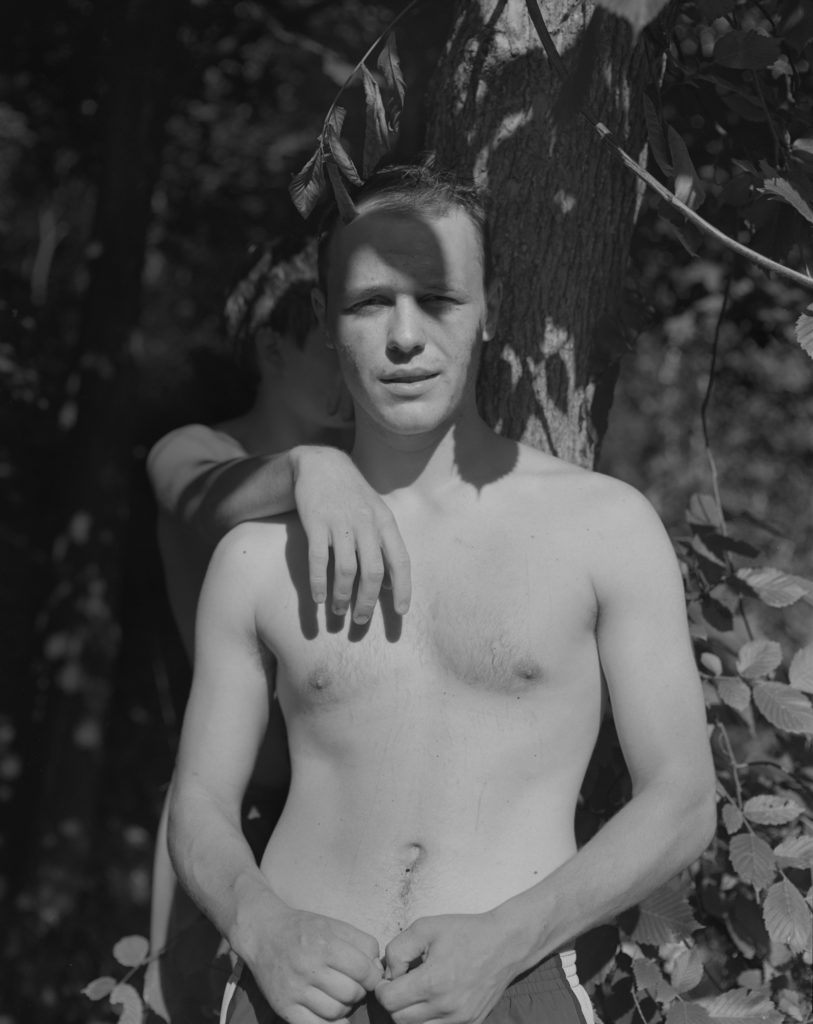

My pictures at the end of the first summer where less intimate. I couldn’t help but be equally enamored by the splendid nature of the surroundings or the way light filtered and fell at various times of day. But as a visual piece, I’m after pictures that are made at intimate distance and convey a visceral experience. After spending a few summers as a constant and familiar presence, wielding a camera while trying to blend in with trees and rock outcroppings, I was permitted to photograph in close space with many of the local visitors at Furlong. This took time and by the third summer of setting up each day, I became more of an accepted fixture. It was also essential that I earn my place among the teens by making a jump from one of the higher ledges during my second summer. It was an awkward leap and gawkish descent marked by an ungraceful entry (I was bruised for a week) but evidently sufficient to gain the necessary approval and respect.

Where this long term project stemmed from? Ι don’t mean the exact time you started taking photos but the realization of the idea of this book.

From early on, I saw what was evolving in my work at Furlong as geared toward a book. It’s the only form I engage in with the potential to inform a narrative piece that’s not solely of my invention. There’s a collective sense of a story wanting to be born when a subject and a place captivates my interest and imagination as profoundly as the initial summer at Furlong. I’d collected a vast archive of pictures and possible arrangements, so a near-infinite number of possible stories could have been weaved from other edits and sequences. Ultimately, for me, I’m limited to what conveys a particular experience and personal point of view (mine) with the aim of discovering a more expansive, universal meaning buried within.

What do you think all these teens have in common?

I can only gauge from what I think I had in common with my peers at this age, which are the timeless pursuits of earning acceptance, satisfying the desire to be well-liked, connecting and feeling a part of something bigger and which shares a commonality, to ward against feeling entirely alone in an ever-changing body and uncertain world.

Could you share with us some backstage anecdotes from your editing process?

I’m almost exclusively reliant on happy accidents that occur when pictures fall in random proximity to one another and begin to inform relationships on their own. It’s a constant shuffling and re-shuffling of small index-sized prints and praying for serendipitous connections that have the potential to exceed anything of my own devising, remaining alert for clues that arrive in the peripheral field of view; song lyrics or a sentence that rises above others and offers the necessary filtering constraints. It’s a perplexing riddle many of us who tell stories with pictures are attempting to resolve. I often begin to understand, at the very least, what a story is not going to be. I also rely fairly heavily on mundane tasks, such as mowing the lawn, folding laundry or doing the dishes, where I’m demanding less of my imagination and epiphanies have an opportunity to enter.

Some photographers prefer photobooks, while others prepare exhibitions for presenting their work. Taking into consideration your artistic activity, you probably belong to the first category. Where would you place yourself, and why would you prefer this kind of presentation?

Yes, I do prefer the venue of the photo book, the democratic structure of pages that face each other and possibility that two pictures might hold the expansive capacity to collectively, by way of proximity and the sum of their particular parts, to form a third, ineffable and potent impression made possible by their individual contributions. I simply haven’t encountered this type of serendipitous synchronicity in hanging an exhibition of my work, where most of the pictures are in view and can be experienced at the same time.

Why did you name the series Halfstory Halflife?

The title was lifted from a book of poetry by Dean Young, a book titled Bender. The poem itself offers a less relevant relationship with my pictures, but when I discovered the title, it seemed to resonate in a way that was ambiguous and pointed toward what was possible as an expression. It says everything and nothing at all about this transitory time of life.

How come you have decided to publish this body of work with Chose Commune? I am asking because you have had eclectic small-run self published editions.

I was craving a collaborative experience with a publisher who would employ a designer to make a book that was beyond my individual imagination, a particular mode of design and choice of materials. Primarily, I wanted to make a book that would be accessible to a wider audience and work with a publisher that was pushing against some of the conventions of a trade edition book and might be inclined to take more risks. Chose Commune fulfilled all of these wishes and more.

One last thing, in your art making (perception of art in general), what would be the biggest difference between the early stages of your career and the present?

I’m not nearly as clever or imaginative as a photographer. I’m ever more slow to compose and make order of my surroundings. The upside is I’m a much more considerate and intuitive editor. I’ve learned to lean-in with a tendency toward procrastination and make good use of prolonged periods of dormant inactivity where I might also encounter my work by way of periphery. I’ve also noticed how ambition has receded as a catalyst. Where, in the past, I would be more likely to pursue, I now find a willingness to let things come. At the same time, I’m much more demanding of my work now and what I wish for in other works of two-dimensional art or works on paper, that the image would embody elements of chance, improvisation or luck, as well as elements of indeterminacy, which allow an otherwise fixed composition to appear fluid and evolvewith us as we continually re-encounter the image. In short, I’m futilely, somehow trying to get closer to music and dance.

More on his website.