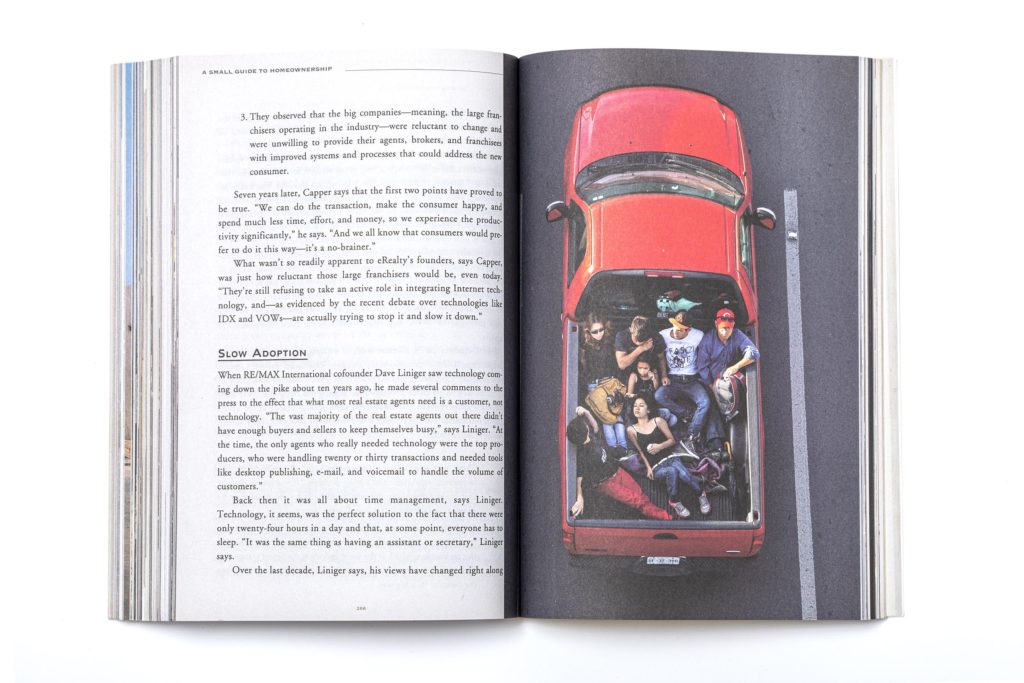

Alejandro Cartagena, Mexican (b. 1977, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) lives and works in Monterrey, Mexico. His projects employ landscape and portraiture as a means to examine social, urban and environmental issues. A Small Guide to Homeownership, published by the Velvet Cell is an amalgamation of 15 years of work, starting with Fragmented Cities series made between 2005 and 2009 in which Alejandro Cartagena documented the suburbanization of the Monterrey metro area in northern Mexico. This project began an exploration that led Cartagena to document the changes that this development brought to the city; from transportation, urban planning, infrastructure development, private and public bureaucracy, the challenges in people’s daily life to the ecological consequences of this unplanned growth.

What brought you to the Monterrey metro area in northern Mexico and when did you create the first pieces of this long-term project?

I came to live in Monterrey in the 1990´s because my mother is from here. We had left Dominican Republic looking for a better situation for the family. I had visited often since the 80´s. Part of the decision to do the project here is because of that rapid change I was able to perceive because I was and am somewhat of an outsider. I started documenting the metro area while working in a photography center as their digitizer of archives. There I had access to thousands of images of my adoptive city and how it had changed in the past century. I guess it was almost natural that I started to work with picturing landscapes and people from here. The archive really pushes the idea of the importance of the photographic document. I was influenced by that romantic notion of bearing witness and images standing the passage of time. There was so much I was scanning of the past that I was looking at in the present that I couldn’t´ help myself not to photograph it. That started this long-term project that is more of an amalgamation of smaller projects that are all interconnected.

In your publication we can see a very interesting hybrid layout, which includes texts, illustrations and infographics. What are the possible dynamics between photography and these elements – how and when do they enhance each other?

The book looks to work in different ways. It is a physical book that portrays common place practices in paper use, (bad) design and layout of usual guides for homeownership. We combined 6 different guides to create our unique version. The decisions of when and where to use what materials was based on the second layer which are the photographs of the many projects I had done. It was an orquestation of the texts and infographics accompanying the images in a way that they would help each other to be more than what they are by themselves. Sometimes we look to create contrast, sometimes it’s a little bit of irony and sometimes it is about creating confusion and dissonance. The book in that sense is made up of a melody (my pictures) and the rest of the book is the musical arrangement… The melody guides the whole piece through repetitions and variations. Then all the smaller elements also happen; cadences, changes of tempo and color, and all the adornments that help emphasize, tense, complicate and harmonize the main theme.

‘A Small Guide to Homeownership’ a long term project, namely 13 years of work. How did you manage to keep up with this over the years? How did you approach all these locations and people?

It started as a small project and it grew as I researched more and more about homeownership, urban development and visual studies. It was a combination of theory and empirical discovery. I would read texts on urban theory and human geography and then do a type of field study of them and find things along the way that I felt would complement the project even better. It was about asking a lot of questions and being alert while being outside photographing. I remember taking pictures of many of the new houses and through finding the best view points from afar I would stumble upon the dead rivers and streams around many of the developments and I started to photograph them. Eventually I would find answers in theory of how the ecological degradation is part of any growing urban settlement of the last 200 years. I was never afraid of it being too much or for it to get out of my control. I see my documentary practice as a lyrical endeavour, where the collisions of different ideas of the same subject matter create new ways to think of it. It isn’t about truth, it’s more about broadening perspectives of how to think of the current state of things and art has that possibility to mix and match freely without the rigour of academia. There is still a commitment to know as thoroughly as possible what you are photographing. This opens up what to do next and how to make a more holistic project. But in the end you’re not trying to be scientific. You’re pushing the boundaries into how to see and think what you are interested in. The book is a perfect culmination of my documentary “cubism” as it contains everything together and forces us to see the interrelationships that are being suggested.

“It isn’t about truth, it’s more about broadening perspectives of how to think of the current state of things and art has that possibility to mix and match freely without the rigour of academia.”

May I ask you for a backstage anecdote or something that determined you, through the production or research of this series?

Let’s see. I got married, did a masters in visual studies, taught at University, had two kids, got divorced and then got together again with my ex wife, finished my 4 years of psychotherapy and went into a pandemic by the time the book was published last year. How do you put together something when the maker is in the midst of so much change? I think for me I have found a really good place in my practice by making things in collaboration. I´ve worked with my editor for the last 10 years, Fernando Gallegos, and the shared anxiety to make the best possible cultural product every time makes for hopefully more sophisticated ideas and products.

Some photographers prefer photobooks, while others prepare exhibitions for presenting their work. Taking into consideration your artistic activity, you do both. What do you enjoy most and how do you decide which one best suits your project?

I was just talking to Fernando about this today. We were asking ourselves if there is a parallel book like Parr´s and Badger´s The PhotoBook; A History about photographic exhibitions? And why we are talking about this is because we have this huge dilemma about what makes photography “become” art, especially when you have so many vernacular photography examples that are amazing aesthetically and technically. Long story short, I think that was is happening is that the photobook has become a place were authorship has to be enforced in such a way that it can make or destroy a project and it is in that gesture that the photographer takes the images he has made and impregnates them with a fixed meaning and narrative. Can you do that in an exhibition space? I think yes but it is something that hasn’t been documented too much but that certainly in the past few years has expanded to become almost art installations to somehow supplement the simplistic act of just putting 10 images on black frames in a row. In the end, I am interested in spaces, books or walls, that offer me an opportunity to expand my photographic authorship from just taking pictures to creating a suggested narrative where I´ve decided where it starts and where it ends.

What would be your advice for a young photographer who wants to publish his first book? Likewise, what is your opinion about the self-publishing that is constantly emerging in the last decade? What are the pros and the cons if we do the comparison with the publishing houses?

If you’re looking to make a book, try it. I would stick to physical dummies as much as possible as your final product is an object. I would look for options to publish with a publishing house as it is a lot of work to self publish and distribute yourself. That being said, you can also make small print runs and not invest too much time and money. What you get with going with a publishing house is their experience and collaborations between the different players (designers, editors, printers, public relations specialists) all packaged into a fee. If you do it by yourself I would recommend you emulate those “filters”; look for a designer, editor, printer that will be willing to put their names on the book and so they will do their best to do a “good” job. Find ways not just to do a book but to do a cultural product that isn’t just a best hits kinda thing. Look to create an object that makes sense as a book and that has intrinsic values that only the book form can offer…materiality, sequence, design. Think of doing something that will not work on the wall… that it is only fixed to work for the book object. Embrace the gutter. Cut those images up! That’s what I try to do.

When and where did you get your political consciousness from?

In D.R. I studied at an all British teacher school in the 80’s and I think the liberal philosophy behind it quietly pushed me to be a critical thinker. I was always out of place with my context there and then even more so when we moved to Mexico. I believe in the idea of culture and how it constructs our beliefs and paradigms. Culture is not art, it is the system of belief we can’t question because it’s so engraved in our day to day. It is so persuasive that we fall into things without even knowing. Even knowing that you know has traps, but I do love the romantic idea of creating alternative viewpoints through analysis and action. Bookmaking to me is both an aesthetic endeavour (of picturing culture) as it is a political point of view.

One last thing, in your art making or perception of art in general, what would be the biggest difference between the early stages of your career and the present?

Many of my early works were about an internal struggle with my identity; was I Dominican, Mexican? American!? I was hurting inside and I didnt even know it. Through doing many projects I was able to come to terms with many of those doubts and then I moved on to thinking of myself but through looking outside. I think in a big way, the difference is that then I was confused and had nowhere to go and now I am determined of where I want to go and a bit less confused.

*A Small Guide to Homeownership was the book of the January 2021, in Charcoal Book Club

More on his website