Simen Lambrecht’s artistic approach is deeply rooted in personal and historical narratives, often questioning rigid societal structures and the ways in which symbols, landscapes, and objects shape collective memory. Beyond photography, he works with installation and text to interrogate systems of value, consumption, and representation.

The architecture included in your studies seems to share many parallels with photography. In fact, many people I know — including some of my students who studied architecture — tend to have a broad understanding of photography. Could you tell us how you first became acquainted with photography?

My first real encounter with photography was during my architecture studies, where it was a regular tool to document spaces, textures, and light. While working on my master’s and moving between Norway, China, and Ethiopia, I began using photography more intentionally to document my surroundings. This gradually expanded from architecture to include culture and people.

Over time, I started developing small projects and ideas, and photography evolved from a functional tool into a way of expressing concepts, ideas, and emotions. I’m self-taught and learned most technical aspects, both camera use and post-production, online. At the same time, my background in architecture gave me a strong foundation that still influences my photographic work, particularly in composition, spatial awareness, and attention to materiality. Once in a while someone will see my work and ask if I studied architecture. I always feel caught red handed, as if someone discovered my secret. I am still not sure what it is that makes people ask me that question, but it is inherent to how I see the world.

Later, I became more interested in the theoretical and historical dimensions of photography. I started reading about photographic philosophy to better understand the layers of meaning behind an image. I’ve always been intrigued by photography’s illusion of objectivity, its ability to appear neutral while carrying implicit narratives. This ambiguity continues to be central to my current work. The Art Of Living Twice is a soft first expression of that fascination. The photos look documentary-esk, and people have wrongly referred to it as a documentary project, but the narrative is quite the opposite. I’m still learning, and that ongoing process is part of what keeps me engaged.

The theme you explore in The Art Of Living Twice touches on metaphysical elements, and, in my view, avoids dwelling on the lamentation of impending death. While you employ various artistic media, what led you to choose photography (and text) for this project? Could you share how you approached the idea of ‘photographing a second and third time,’ keeping the same concept in mind?

I guess everything can be thought of in metaphysical terms, and I would argue that all art invites metaphysical interpretations. So in that sense I am following that tradition. It is easy to see the project as an ode to my grandma, and to some degree it is precisely that, but beyond that it is also about searching for a broader understanding of memory and remembrance. The choice of photography felt natural because the medium carries a relationship to time and memory.

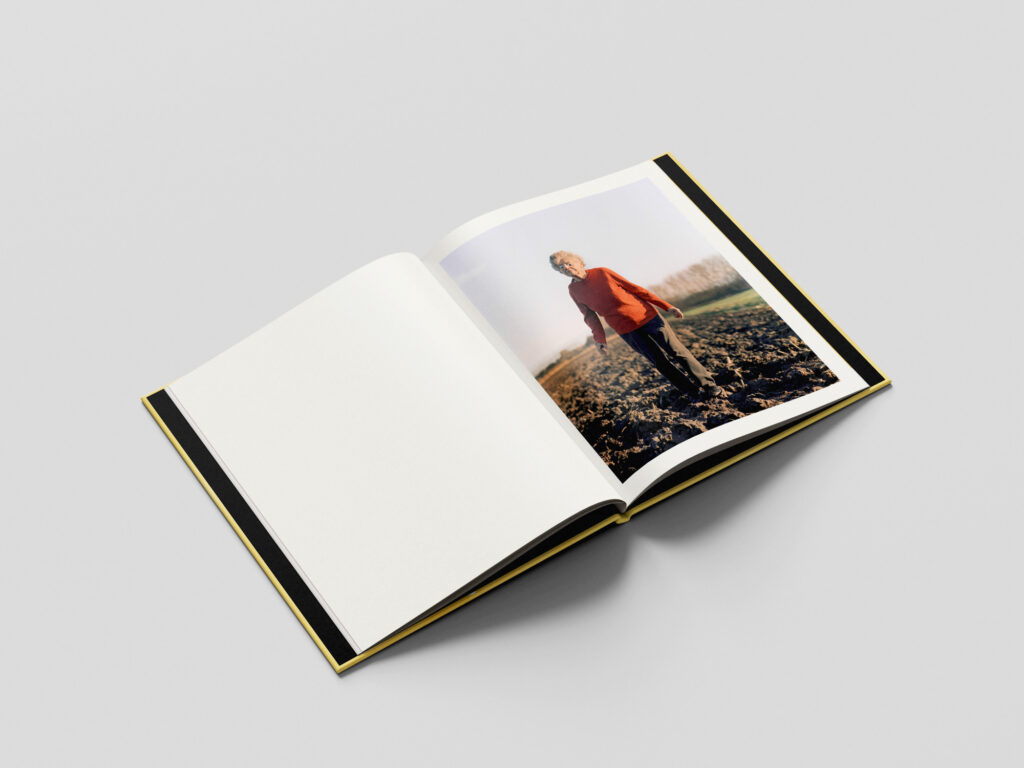

I enjoyed playing with the idea that the photographs are on the very edge of the documentary tradition. Most of the photos are staged or are recreations of memories and are therefore subjective. But since the project is about my interpretation of reality in the relationship with my grandma they all are the truth. Photography helped me find that edge, which would be impossible in painting for example. That is also why I chose to exclude any images of my grandma in the project or work with other archival images I have of her. The images are all made after she passed away.

The project is not about death itself, nor about the fear of it. Rather, it sees death as the beginning of a new kind of relationship, one that exists beyond physical identity or need. Throughout the process, I focused on the relationship I continue to have with my grandmother, one that has been taking shape since her passing. The work explores how a bond can renew and transform in the absence of one person.

The text in the project was a guideline to the images. They came before Cecile’s passing and are the only thing that is directly of her, where you can still understand her person before she died. As they are an important part of the project I wanted to include them in the publication, and hope they can form a conversation with the images. It would be a conversation that is held on either side of death, which I find quite beautiful.

What are the possible dynamics between photography and text? How and when do you think that they enhance each other?

I think of photography and text as parallel languages, neither should necessarily explain the other, but can make for a more holistic experience. In The Art Of Living Twice, the text is kept intentionally sparse, and is highly curated by me. I chose to curate heavily to have the words reflect my relationship with my grandma. If someone else in her life would choose the quotes we would get a very different idea of her as a person. As I said, the goal is not to show an objective mirror of my grandma as a person, but rather my experience of her. Nevertheless, the words offer anchors for the images and influence them greatly. I think text and images work the best together if they add a different angle to the same focus.

How can meaningful communication be built between people from two different generations?

When I was younger my grandma was a caring figure in my life. She would pick us up from school, make food, help out with daily tasks and listen to our stories. Which is, however nice, quite a one-dimensional character. It was only after I left Belgium for university and we began exchanging letters that she became a more rounded persona, someone with hopes, dreams, love, and heartaches. Realising that my grandmother was once the same age as I am now was in a strange way, mind-boggling. In the same way that at some point you can see the flaws in your parents and realise that they, too, are just people. That was the key to bridge an age gap I think.

The letters weren’t meant to be art, but they became a form of collaboration. Her way of writing, recalling, and observing gave me access to a world that was both personal and historical. Communication between generations takes time and it doesn’t always arrive in dialogue.

I saw that your recent crowdfunding campaign for the photobook of this body of work was successfully overfunded—congratulations! What led you to choose the book format as the way to tell this story?

Thank you! The book felt like the most intimate and sustained way to tell this story. Unlike an exhibition, the book allowed for silent unfolding. It could carry the rhythm I had in mind, intertwining image and text one by one. I also wanted the viewer to be able to return to it, to keep it close, hopefully pick it up again once in a while.

We’re also making a conscious effort to keep the price low, so that as many people as possible have the opportunity to access the book. Later on, I plan to release a free PDF version online for anyone who’s interested, regardless of budget or location. That said, I enjoy the analogue experience of a book. There’s a physicality in turning pages that mirrors the act of remembering. The simple one-image-per-page layout of the book emphasizes the distinct character and narrative of each photograph.

Has the work been presented in physical exhibitions or gallery spaces? If so, is there a moment or an installation view that you feel captures the atmosphere you envisioned?

Yes, selected works have been shown in both group and solo exhibitions, locally and abroad. Each place where the work was shown was important in their distinct way. But bringing the images back to my grandmother’s village meant a lot. I was able to present the project to her friends, neighbours, and family, it was somewhat of a full circle moment.

I found a farmer in the village who let me install billboards on one of his fields, right next to a small bicycle path. The vernacular aesthetic of the billboards, combined with the agrarian background I grew up in, made it special for me. The boards are still standing there, although the corn that was planted has now obscured the view of the images. In a way, it feels like a poor metaphor for returning and becoming rooted in a place you once left.

You use Kodak Portra 400 throughout much of this work. How do you approach post-production in this project? What role did it play in shaping the final images?

Portra 400 is well known for its beautiful (light) skin colour rendering and gave me a baseline of softness and warmth that I felt aligned with the tone of the project. I try to avoid heavy post production, the infinite amount of corrections you can do makes me nervous. I mostly cleaned up the dust and other inconsistencies in the scanned image, and left it there. I used to be more of a purist, and believed you should limit post production as much as possible to get more valuable images. I don’t really believe in that anymore, but I enjoy getting the image as close as possible to what I want straight in camera.

At what point did you feel the project had reached completion—and what made you decide it was time to put the camera down.

I don’t think there was a single decisive moment, but rather a gradual sense of satisfaction with the work. At a certain point, I had around 500 images and felt the need to organize them. I selected the ones that felt most relevant, and filled up the gaps between them pragmatically. I also felt that the emotional arc had settled, and my new relationship had formed. I still have a list of images that I believe would work well within the project, and there’s a good chance I’ll still make them. But they may end up in another project, or simply remain personal mementos. I think it’s nice to occasionally create images that I know only I will ever see.

What is the most significant contrast in your perception of art(making) today, in comparison to your initial days at university or when you took your first shots?

I’ve become more comfortable with ambiguity. In the past, I wanted to define meaning, to be understood, to arrive at a singular truth or logic. Now I see that pursuit as quite futile, and often led only to frustration. I’m more drawn to what resists explanation and invites reflection. For me, the role as an artist has shifted from being a pure creator to becoming a translator, or at times simply a witness. I don’t feel the need to impose a singular meaning onto the world. Instead, I try to observe, and react or respond to it. I attempt to make sense of emotions, rituals, and fragments of experience that I find bizarre or interesting. This shift has allowed me to work with greater openness, and to embrace uncertainty as a meaningful part of the process.

My definition of success has also changed significantly over the years. I define and redefine it daily. One day, success might mean getting out of bed; another day, it could mean finishing a project or publishing a book. Success only holds meaning when it’s connected to time and context.

More on his website