Born and raised in Germany, Birthe Piontek moved to Canada in 2005 after receiving her MFA from the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen, Germany. Birthe’s art practice explores the relationship between memory and identity, with a special interest in the topic of female identity and its representation in our society. Abendlied, her recent publication, was a great opportunity to have this conversation.

You have taken pictures of your family whenever visiting Germany for a quite long period of time, since you moved to Canada. When did you create the Abendlied series? Did it come naturally as you were reviewing-sequencing your photographs or it had a certain starting point?

I worked on the series for about seven years – from 2011 until 2018. In the first two years, I wasn’t sure what I was doing; little was I aware that the project might end up in a book. I just had the urge to express what I saw and felt when I visited my family in Germany. It was the time where my mother showed the first signs of Dementia; however, we weren’t sure about that back then, or better: we were in denial. But something was shifting; she was slowly slipping away, and so was the house I grew up in. After two years of working on the project, I found that I had started to develop a visual language for what was going on, and I also knew what I wanted to say. However, like with any project, it takes a lot of trial and error and a lot of time to refine ideas and images. It was especially challenging as I wasn’t physically present on an ongoing basis and only had a few weeks each year to work on it. But in many ways, the breaks were also useful to digest what I worked on and let ideas simmer.

I particularly like this part of your artist statement that gives a lot of attention to the “unspeakable that is unique to each family”. How did you manage to create photographs that are open to interpretation and not just family commemorative materials and finally let us, the viewers, delve into this?

That is a good question, which I’m not quite sure how to answer as I’m not entirely certain how I managed that. I’m glad to hear that the viewer can delve into it. For a long time, while working on the series, I was afraid that this might not be the case, that the images would be “too personal” and the viewer wouldn’t be able to access it.

I think, as much as this project is a personal one, it is also very universal. In many ways, the materials I’m working with are universal, too, even though they might have a specific meaning for my family. But the viewer knows what these materials are. One knows about the symbolic meaning of collected teeth, hair, or precious porcelain. We all have versions of these mementos in our homes. And, at some point in our lives, we all encounter losses and the accompanying grief. We understand the power and workings of change and we understand when something comes to an end. Maybe, it’s not so much the materials, but the universality of these experiences that make it possible for the viewer to enter the work – and feel it.

We can notice that you are working on long-term projects. How do you decide the perfect timing to put down the camera and publish the work?

There is never a 100% clarity, or an “Aha” moment. When working on long projects, the most draining part is the “fine-tuning” or “rounding-out.” When you have a lot of material, it’s more difficult to figure out what is missing. But then you enter a phase where you start repeating yourself, and that’s when I know I’m reaching the end of a project. In the case of this particular project, it was a lot more straightforward and related to external circumstances. I always knew that this project was about my childhood home – and my mother. When the house was sold, and my mother wasn’t able to collaborate in the photographs anymore, due to the progression of her illness, I ended the project. But by then, I also felt I had said everything I needed to say.

Some photographers prefer photobooks, while others prepare exhibitions for presenting their work. Taking into consideration your artistic activity, you do both. What do you enjoy most and how do you decide which one best suits your project?

I enjoy both. And for almost every project, I’ve always tried to find iterations for both approaches – book and exhibition. But usually one comes before the other. Abendlied, Lying Still, and The Idea of North were all conceived as books first, and afterwards, I thought about a possible translation to the wall. All three projects are quite substantial in regards to the amount of images, a fact that lends itself more to the book format than to an exhibition. Lying Still consists of found images and my own photographs; together, they weave a multifaceted dialogue and create a narrative throughout the book. In Abendlied, there is a sense of progression of time – at least that’s how the images are organized. Similar to Lying Still, each image builds on the next one, and there are many cross-references. This sort of “weaving” of a story that has complexity and a certain density translates better to the book format. An exhibition of these projects will never reach the same complexity but is still important as here one has the opportunity to encounter the work in a different scale, in a different spatial organization: the viewer is “confronted” by the work and doesn’t hold it in the hands. That’s a very significant shift in perception and engagement. And, then, last but not least, there is my other work that is sculpture and installation-based. These works were obviously always intended for an exhibition space – however, some also live in a book format. Here they are paired with poetry, which gives them another layer of meaning.

You are a member of the Cake Collective. Can you share some info about it and how do you feel being part of a collective?

The Piece of Cake Collective was founded by Charles Freger in France in 2002 as a network of European photographers. In 2009 it “expanded” to North America, where is it is now called Cake Collective. We currently have members in the United States, in Canada and Mexico and are always in dialogue and exchange with the European members as well. Being an artist can be a bit of a lonely experience. We often find ourselves making work on our own and once out of art school, critiques and conversations about work are hard to come by. On top of it, we usually apply for the same resources, i.e. stipends, awards etc. which sometimes can create a sense of competition instead of comradery. The Cake Collective counteracts all of this. It’s a community of people who want to share: thoughts, ideas, work, resources, meals etc. We come together twice a year for workshops where we show each other work, get involved with local artists or art institutions and try our best to support each other. By now, the Cake members have become some kind of a “photo family” for me. Especially in times like these, where feelings of isolation and anxiety are part of our daily lives, it’s wonderful to be part of a community that has your back.

What are you working on now?

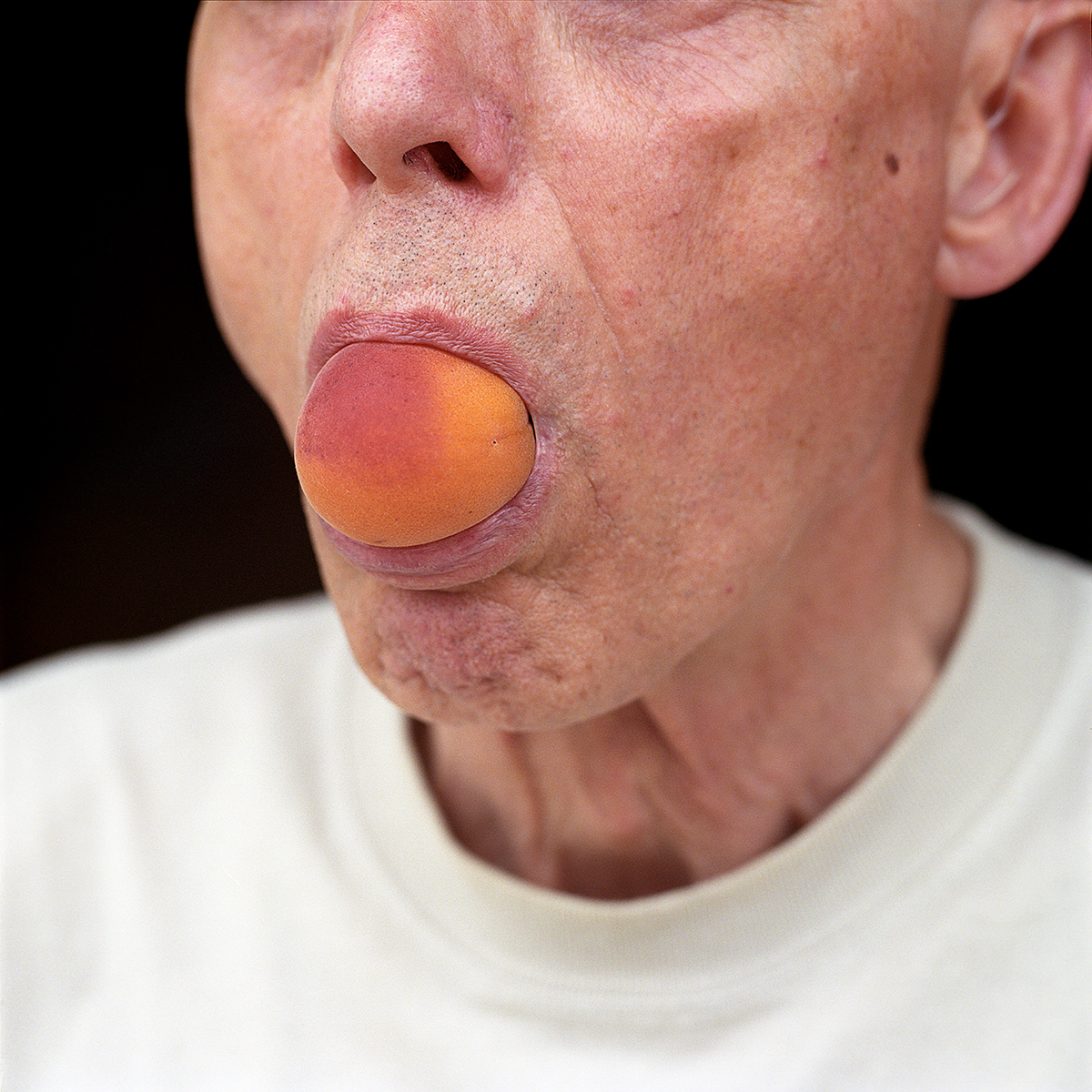

I’m currently working on different projects. One is called Janus – a playful investigation into the genres of still life and the domestic, combined with aspects of performance. The series revolves around the ideas of growth, metamorphosis and decay. Compared to many long term projects, this one is actually “short term” and, in many ways, more spontaneous than previous works. The other project involves again found/vernacular images that are manually transformed in the studio and then rephotographed. For a long time, my photographic practice has been inspired by and combined with a sculpture practice. I’m very much interested in understanding a photograph as a malleable object while trying to draw out its content and materiality into the 3-dimensional space.

You have a wide body of work and a lot of experience as an artist. In your art making (perception of art in general), what would be the biggest difference between the early stages of your career and the present?

In the beginning, after I finished my MFA, I never thought of myself as an artist, and the career I pursued was one of an editorial photographer. Although I didn’t consider myself as a documentary photographer, I was interested in telling stories through my images and working for magazines, taking portraits, meeting different people and glimpsing into their lives seemed like a perfect fit. Over time I found working in this way a bit limiting and I also found my visual language to become limited and stale. Maybe it was also a time where I lost faith in “traditional,” straightforward photography. And while I questioned the power of photography, I found myself wanting to work in a much more tangible way; I wanted to create something with my hands. This was when ideas of collage, installation and sculpture started to seep into my practice, and I realized I had transitioned from a photographer to a photo-based visual artist, which is what I think I’m today. A few years ago, I also started teaching at Emily Carr University here in Vancouver. Taking on this position introduced a big shift into my practice and my visual language as I get a lot of inspiration from working with my students.

More on her website.