Description

Robert Darch’s latest work, Vale, presents a distinctly unnerving and disorientating experience.

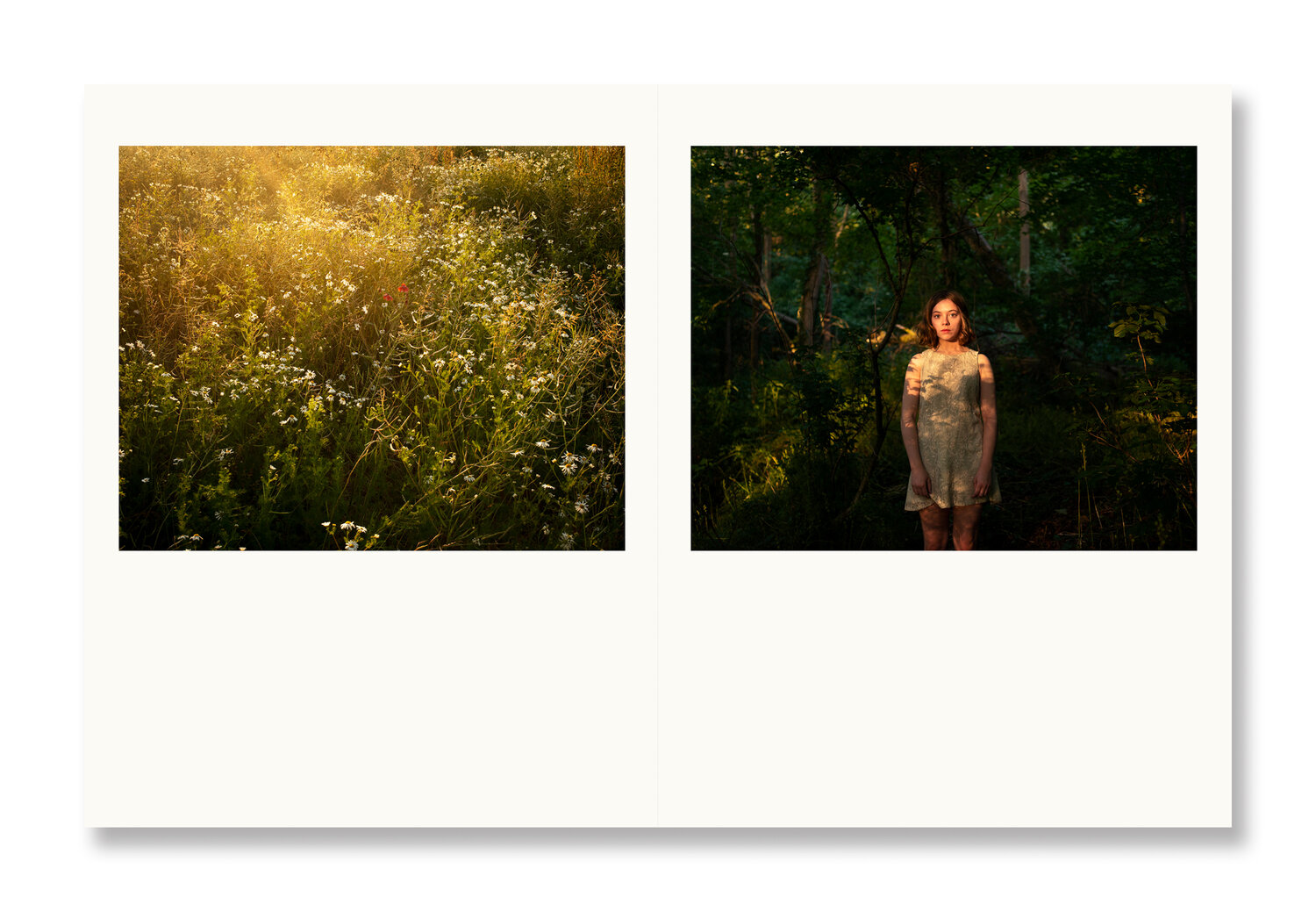

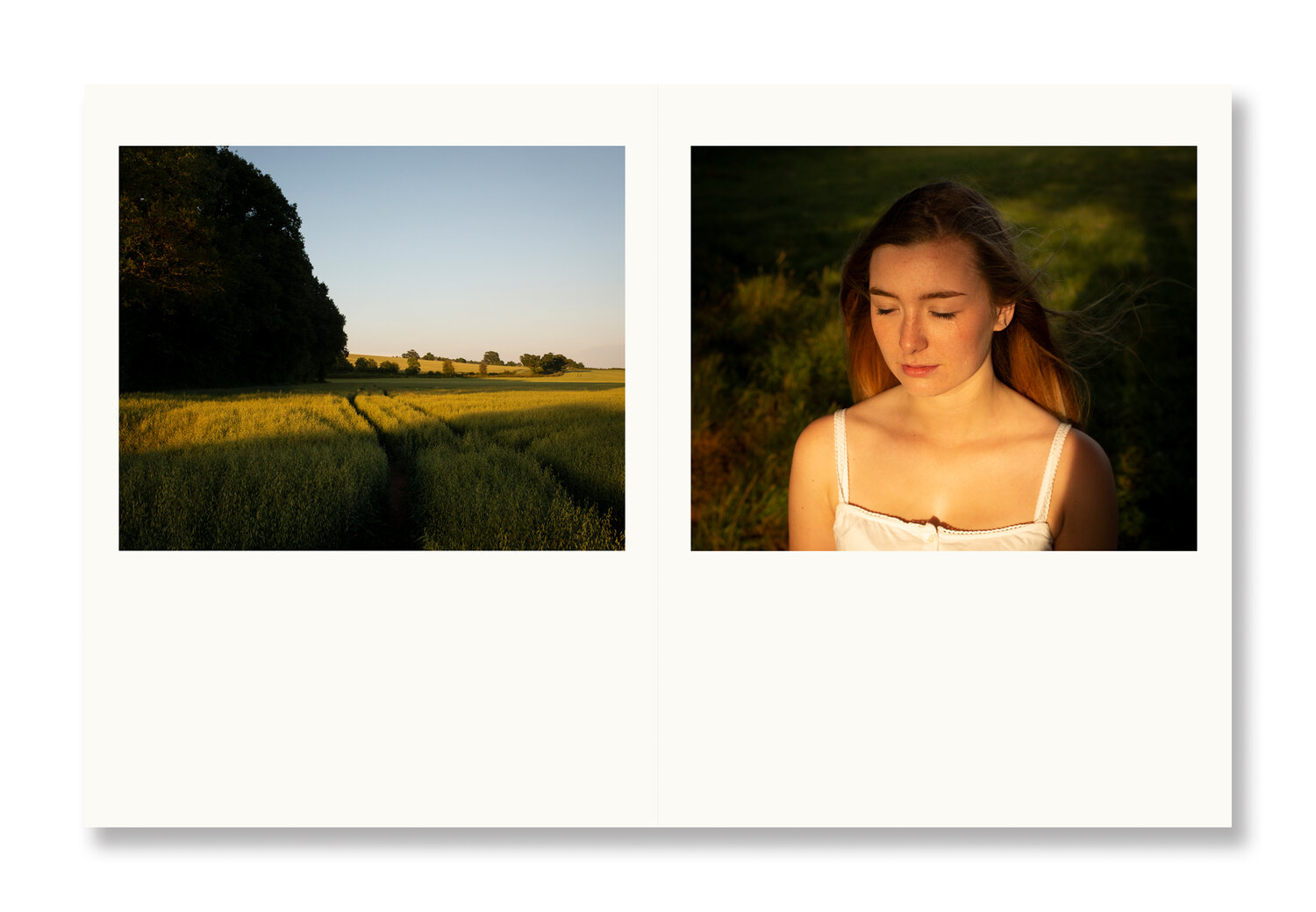

The expectation of a rural idyll is created from the outset; an archetypal English valley landscape pulled from a perfect composite memory. But this beauty is quickly undercut, disturbed by a cast of characters who seem unwilling or unable to play along with this bucolic vision. Darch has created a space where something else, below surface appearances, is happening.

At the age of 22, Darch suffered from a minor stroke, followed by a period of ill-health which would affect him for the majority of his twenties. As a coping mechanism during convalescence, he retreated into a world of fictional narratives, of indoor spaces and eventually a physical move back to his familial home of Devon. Slowly, he began to reset his narratives, his place in the world, and the expectations of his youth. An unseen enemy threatening his own body and psyche was mitigated by escapism and wish-fulfilment.

The fictional worlds into which Darch escaped, exhibited characteristics which were at once benign and threatening. An interest in the English sense of the eerie had been with him since childhood, notably the writings of James Herbert, the Dartmoor of Conan Doyle and such touchstones of ‘coming-of-age’ cinema as Rob Reiner’s Stand by Me. As Darch’s period of retreat from the world lengthened, further influences were incorporated into this mix, from British standouts such as Jonathon Miller’s Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968) to the Italian Giallo film movement of the 1970s and the atmospheric and psychological Japanese horror revival of the early 2000s.

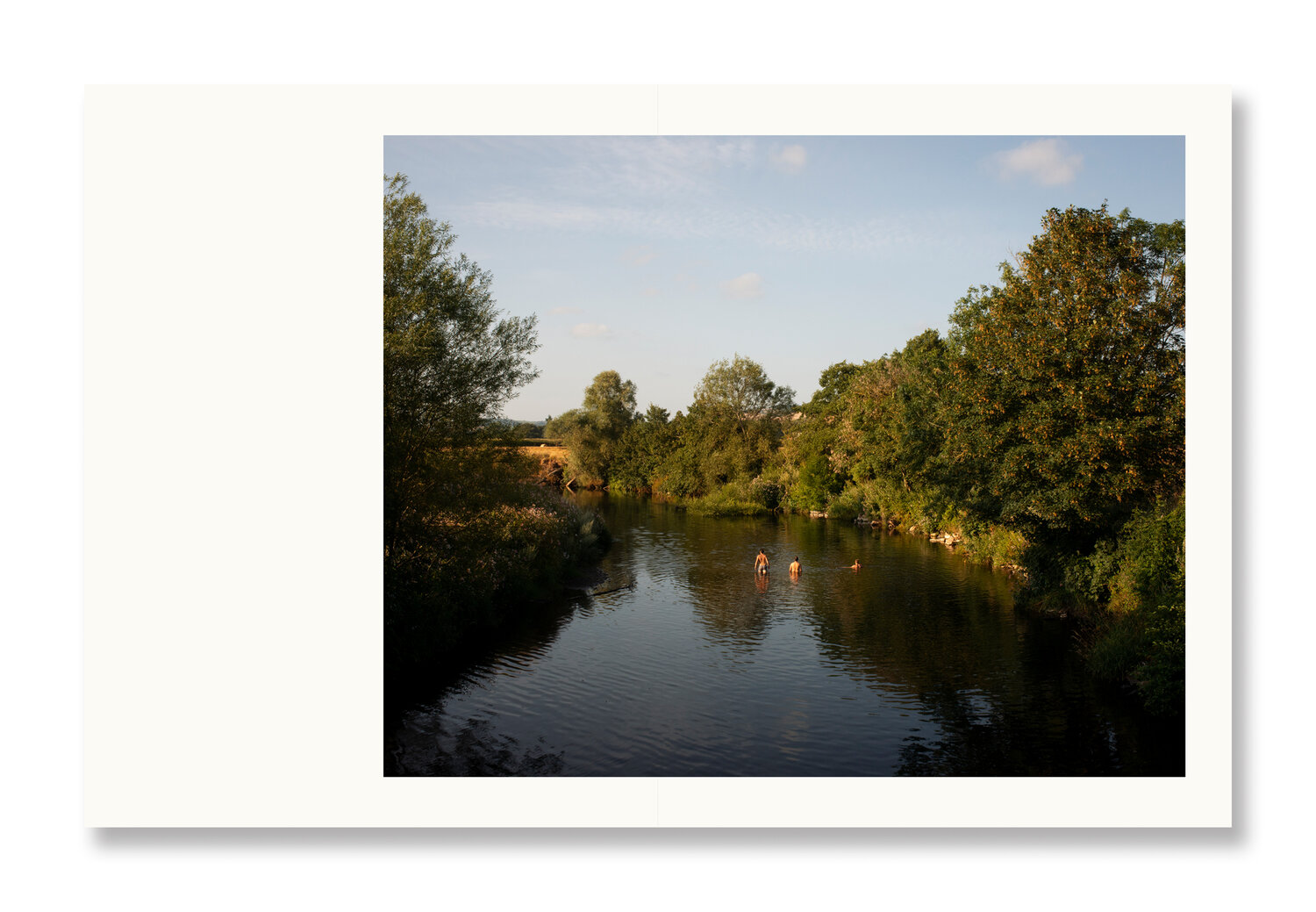

Vale is a result of this percolation and loss. It is the fictional space where Darch is able to relive and re-imagine a lost period in his life, journeys with friends both through physical spaces and through time. On one level its subjects could act as stand-ins, allowing him to explore winding rivers in late summer evenings, empty country roads and ancient English woodlands. But as the journey continues, multiple readings quickly become apparent. Despite possibly providing a positive escape from Darch’s ‘vale of despond’, it is the sense of the eerie which becomes unavoidable.

The notion of the ‘eerie’ has a long history in British landscape art, yet its specific manifestations are particularly difficult to pinpoint in still photography. Single images by Bill Brandt, Raymond Moore and Paul Nash have previously illustrated the capacity for the eerie within the British landscape. Still, the extended narrative version of this feeling has often fallen into the sole domain of the moving image. In his previous work, The Moor (2018), Darch also experimented with a sustained sense of the eerie, the ominous, but this was a more stable presence throughout. Vale is, interestingly, an altogether less immediately comprehensible space.

To further complicate the matter, feelings of serenity and eeriness are often close bedfellows, and without the audio cues often employed within film, this definition becomes an even subtler distinction. A‘which feels emptied rather than empty’, a sense which is all the more ‘monstrous precisely because it will not demonstrate itself.’. Darch’s Vale straddles both sides.

(‘Walking in unquiet landscapes’ Robert Macfarlane, https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-36-spring-2016/walking-unquiet-landscapes, 2019)

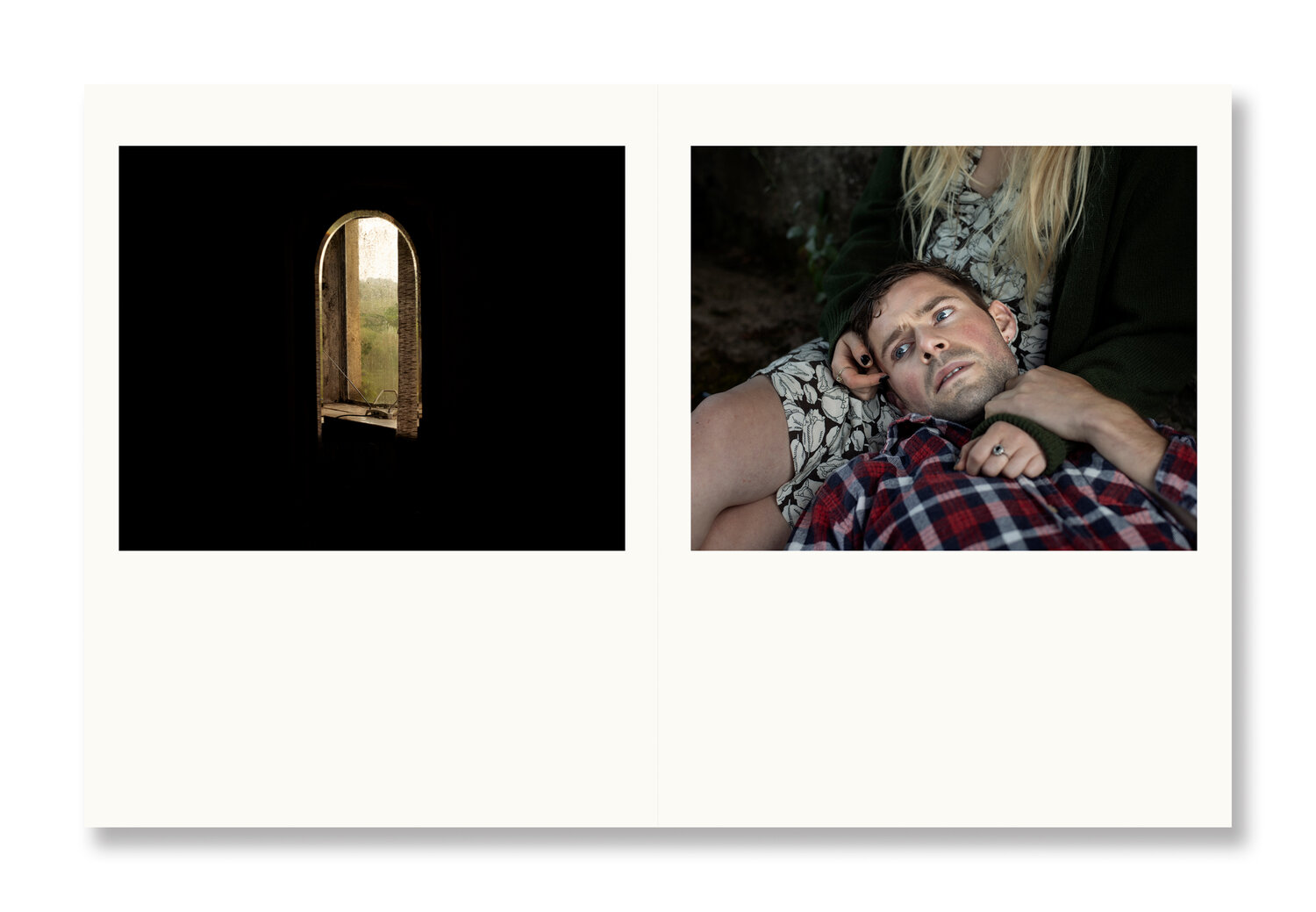

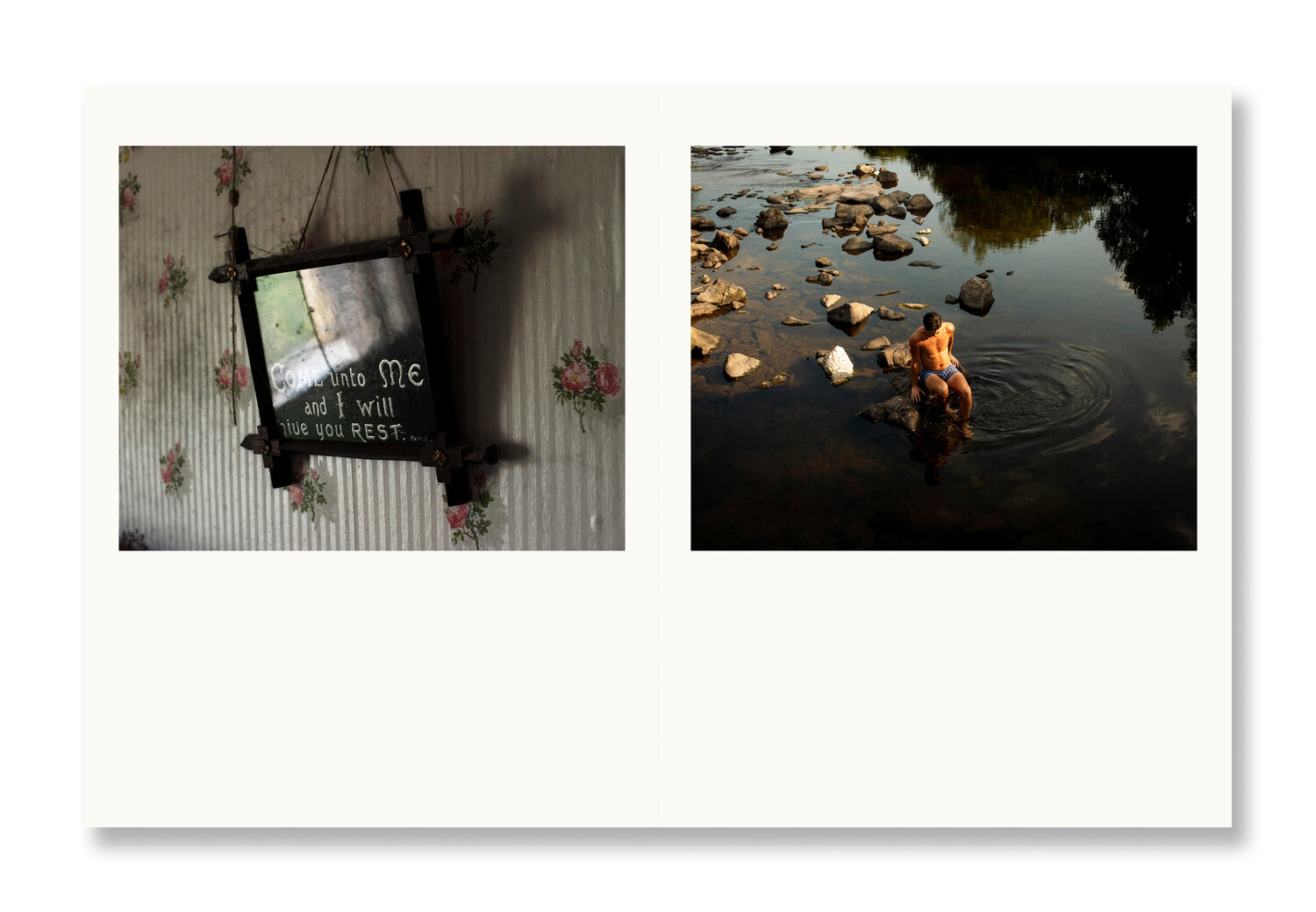

This brings us to the central conflict within Vale: an uneasy duality created by Darch through his choice of locations contrasted with the characters he places in them. We see the figures, almost from the beginning of the sequence, either ill-at-ease or else staring back at us, at the photographer. Defiantly, they appear to be questioning our motives within this fictionalised world. This dialogue is hinted at and expanded upon throughout Vale, and questions abound. Is that the spectre of the observer we can see in the window of an abandoned building? Might there even be some sense that the photographer is envious of these characters?

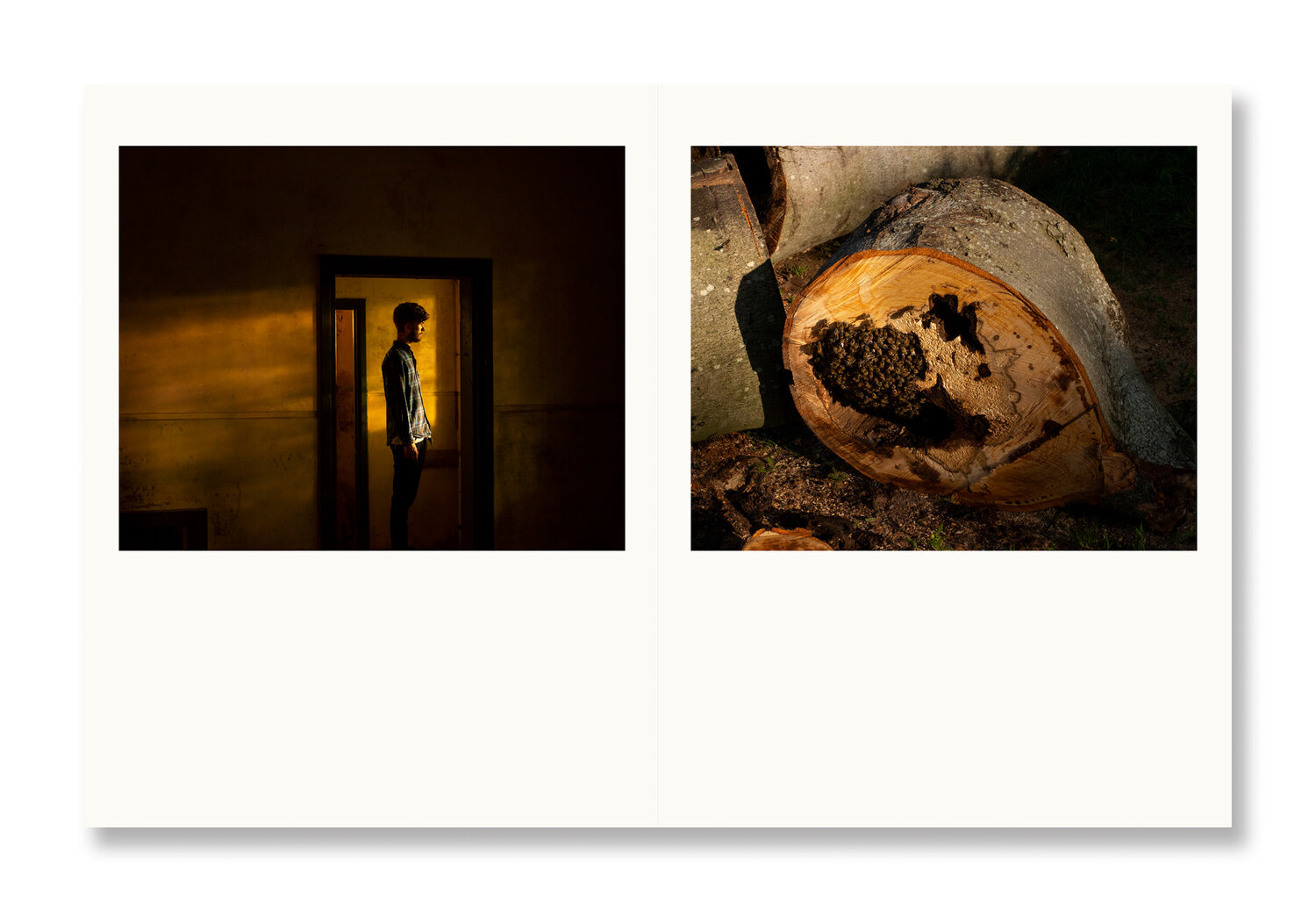

Further choices made by Darch add to this layered conflict. Even the characters’ clothing and their inherent youthfulness – a Spielbergian world of plaid shirts and summer dresses – evoke the appearance of innocence and purity. But this duality becomes unbalanced, and it is the feeling of unease that comes to dominate. Indeed, in this sense Vale can be seen as influenced by the structure of Stand By Me, where the initial sense of safe peril, and the joys of youth, move inextricably towards a darker path. But Vale then becomes darker still, something more akin to a Dario Argento horror film set. Darch’s use of harsh light and the sharp focus on abandoned domestic spaces which perhaps hide cruel intent and decay, further signalling the possible collapse of this world.

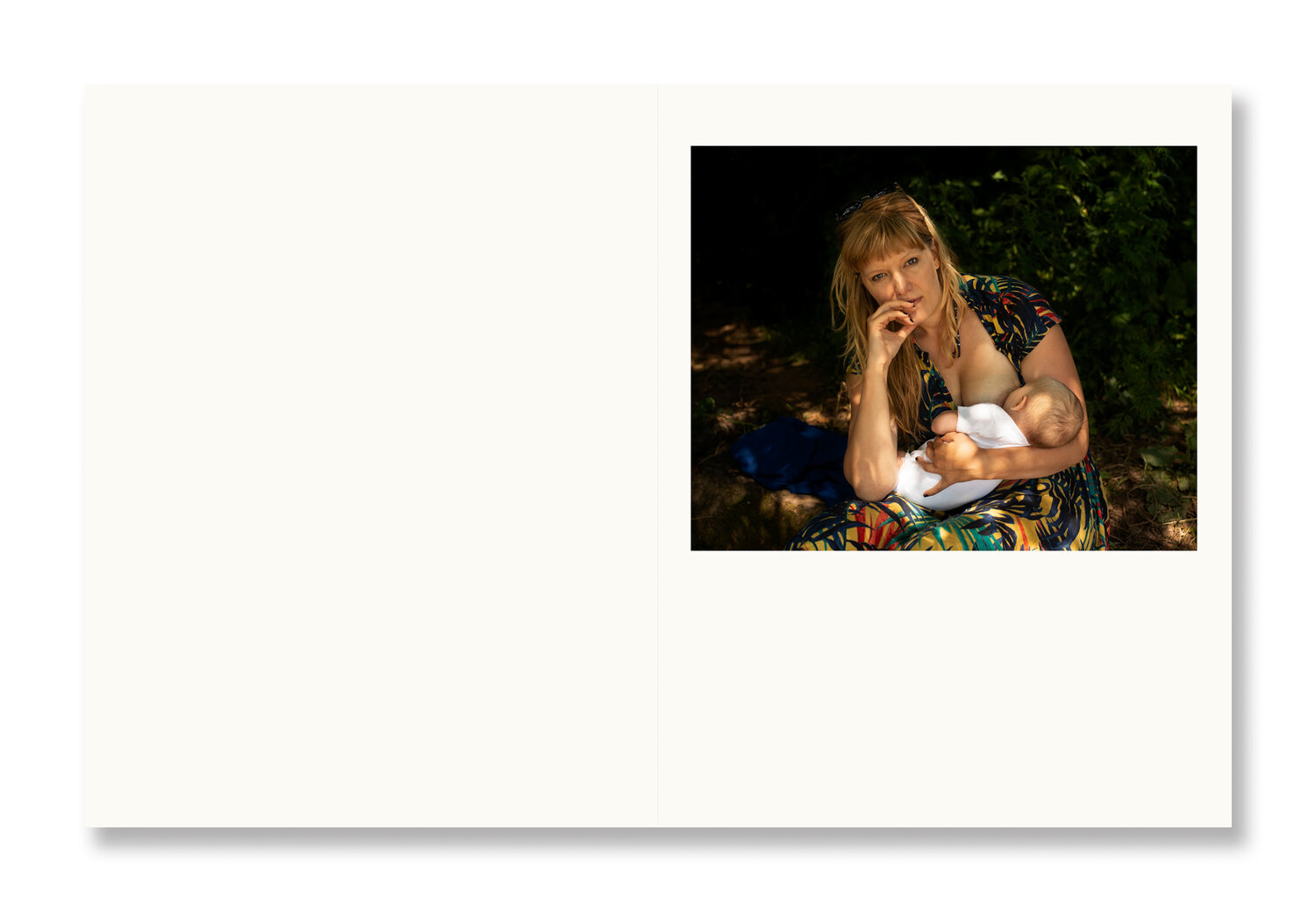

One of the central images shows a mother breastfeeding her child, a sole figure of maturity among a kaleidoscope of youthful faces and bodies. It is possible that she is a reminder of the upcoming realities of adulthood, but even in this beautiful image of nurture and calm, she is reminiscent of photographer Dorothea Lange’s famous Migrant Mother (1936). A further allusion to a past world that was harsh and unforgiving.

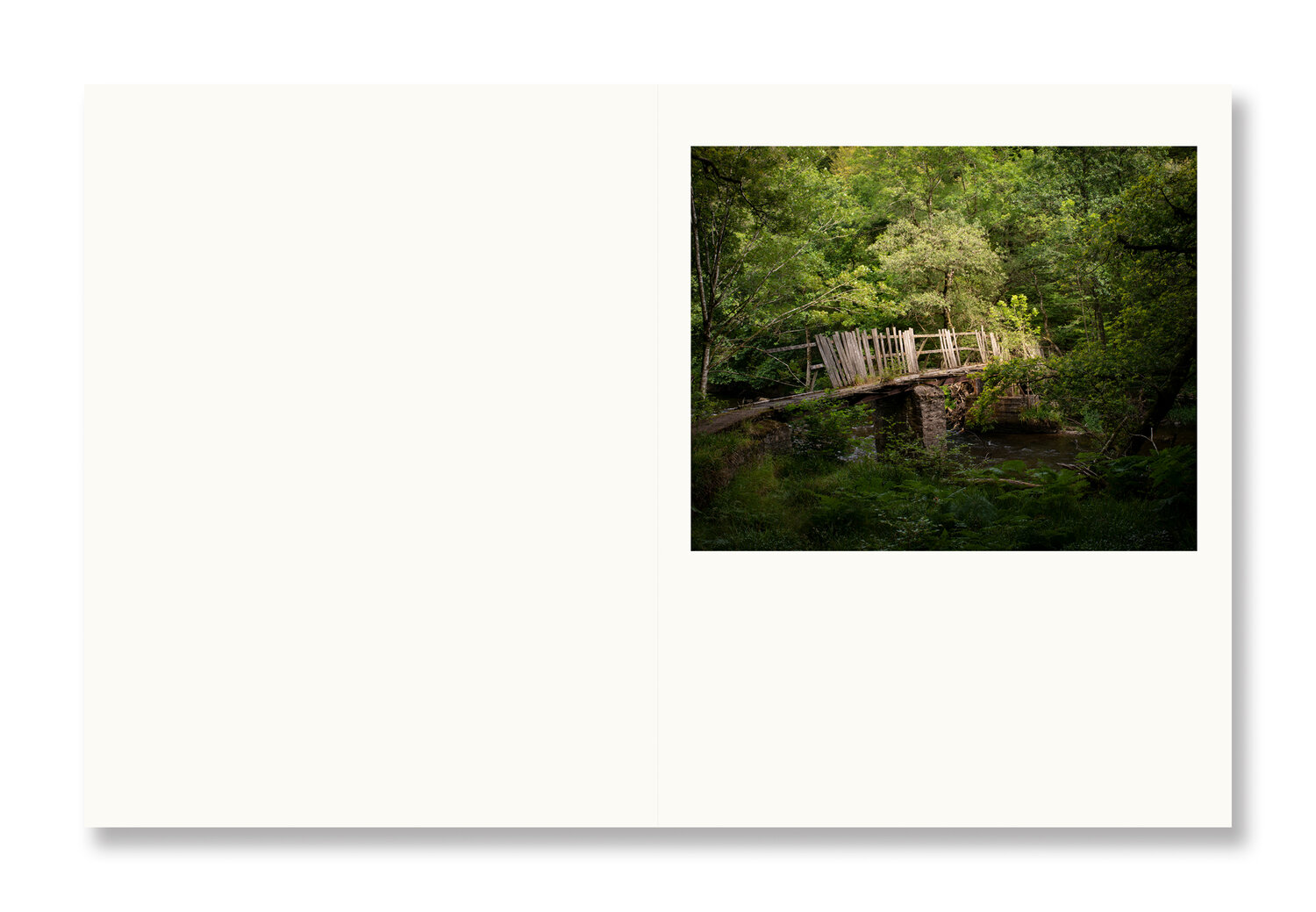

As the sequence of Vale continues, Darch’s projection of the loss of his youth becomes too much for his subjects to bear. So, despite, or perhaps because of, the beauty of these images, it is the constructed nature of this world and its origins that inevitably weighs on them. Even the landscape itself gives away indications of artifice: a bridge collapsing, a diseased tree seemingly being held up by a hunting ladder. As the artifices and pressures build, the images move from implied to explicit unease: a swarm of bees colonising a felled log; or the corpse of a hare, decomposed among the debris of broken glass. A change in the palette of the images, another influence from the cinematic, signals this move, with cooler blues and yellows fading into greys, as the space becomes increasingly hostile.

In the liminal space between fiction, narrative and reality, the intentions and outcomes of Vale have become intractably intertwined. However, we must respect the fictional boundaries of this place as if they were reality, even as this world itself begins to fall apart. Indeed, we might conclude that in our current situation within 2020, a sense of a loss of time is what might be driving our own search for the promise of truth that nostalgia seems to offer. But even as we are in pursuit of that promise, we may need to discard the veracity apparently offered by photography, recognising and ultimately embracing Vale as the manifestation of a lost time, with all the weight that such a loss implies.