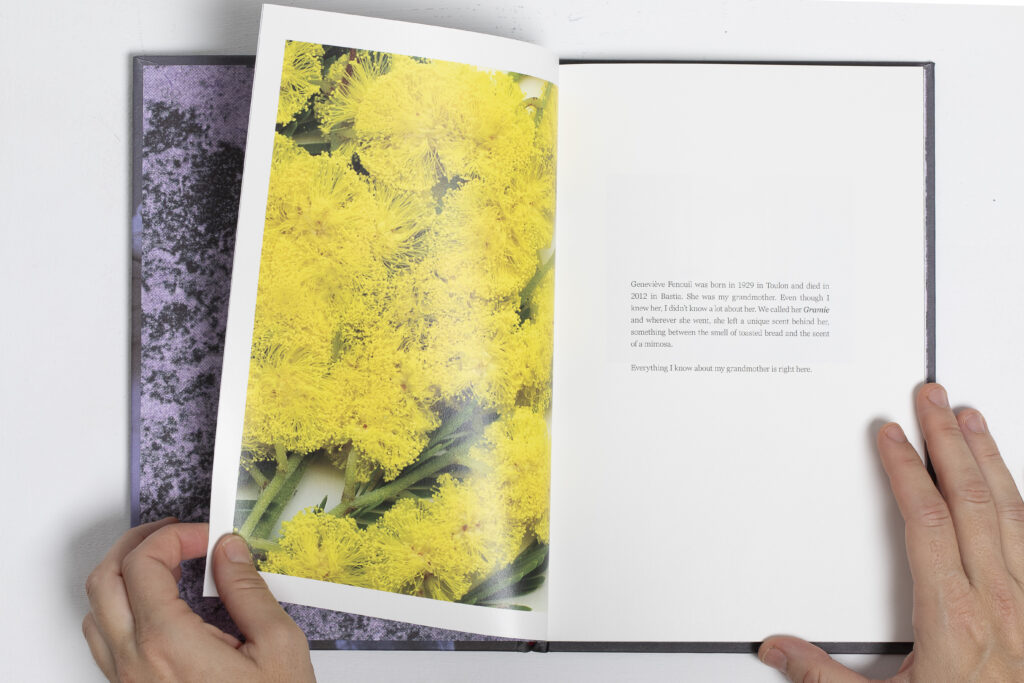

Artemis Pyrpilis has studied photography at the Stereosis Photography School in Greece as well as at the Ecole de Photographie de Paris ICART PHOTO in France. She is currently based in Thessaloniki, Greece and teaches photography. Her artistic practice is mainly expressed through the development of long-term projects that are released in the form of photobooks and/or the pursuit of the possibilities of dance. In 2012, the photographer travels to Corsica to visit for the last time her grandmother, Gramie, who is in the final stages of an illness. This work comes to light, as a photobook, more than ten years after her grandmother’s passing and includes images from their last meeting in Corsica, archival photographs and drawings from a zoology notebook of her grandmother’s, an unexpected legacy that sparked the urge for this publication.

The extensive use of photographic archives in your work first appears in your previously released photobook, Nette (2021), which also focuses on the exploration of your grandmother’s particular characteristics when she was young. However, it seems that your interest in photographic archives didn’t begin with this project; you’ve always been captivated by collections. What is it about this type of material that fascinates you?

I’ve always been drawn to that. I suppose it might have something to do with my father and how he made sure to extensively document and capture our childhood (both mine and my brother’s) therefore creating a detailed archive of our lives. This was always interesting to me as I never knew the real reason behind that and why this stopped at one point. Did he want to preserve the memories? Maybe he wanted to be able show us later on how we were as kids and at one point thought that we were old enough to have our own memories? I don’t know. What I find interesting is the mystery behind an archival image you find lacking context and how this particular moment/image was important enough to capture/preserve in some way. This happened with the archival material I found when working on “Nette”, hundreds of images lacking context, filled with mystery and this fascinated me so I tried to create my own narration around them.

Also, “Evidence” (the work by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel) was one of the first conceptual photographic works of the 1970s, demonstrating that the meaning of a photograph depends on the context and order in which it appears. It showed me the possibility of recontextualizing the photos. It was a game changer for photography because it challenged what we think of regarding originality and authorship and artist intent. These were not only mechanically reproduced images but not even made by artists. It is an homage to the archive. It gave me a chance to explore and to understand photography in a different way.

We often think of our family members solely in terms of their roles in relation to us. Yet, in both Nette and your new project Gramie, we see a dynamic woman who is much more than just a grandmother. She has experienced tender as well as dark moments in her life. How did the eight years of developing the photobook Gramie unfold?

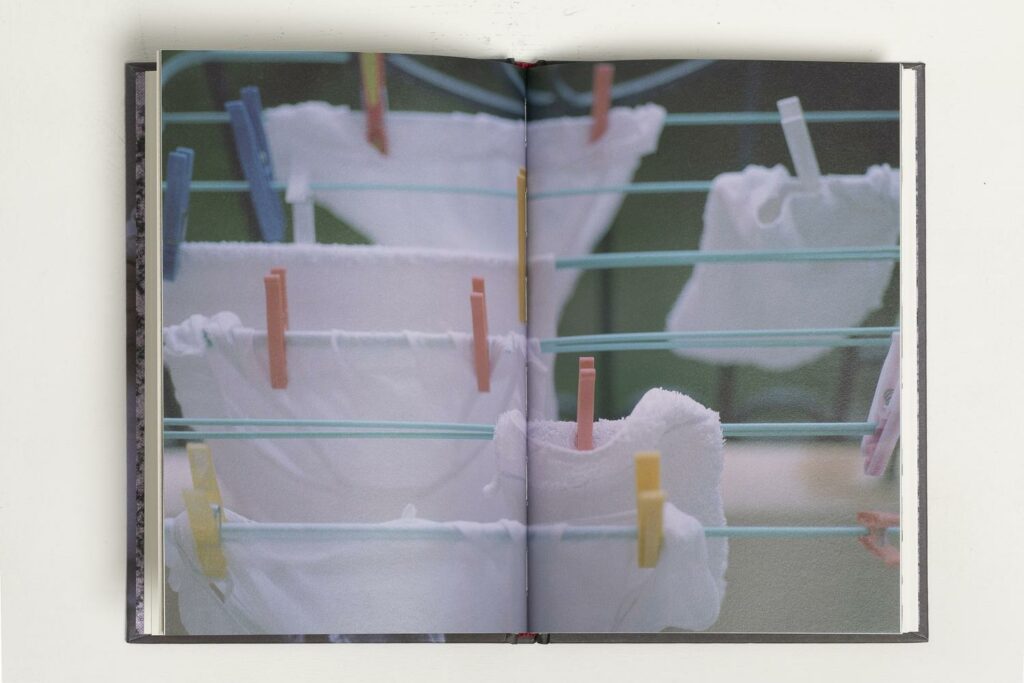

In 2012, I travelled to Corsica to see my maternal grandmother for one last time. She was terminally ill and most of my family members from my mother’s side were there to say goodbye. I still don’t know what made me take my camera with me or even take pictures. I had never photographed any member of my family before nor captured or exposed anything that personal in my life. It was all a blur actually, it happened out of necessity, there was absolutely no intention or thought behind this act. Now I understand it was a coping mechanism and the only way I could tolerate this intensely emotional situation. I never thought of it as a project or even considered creating a photobook. I just felt I had to take these pictures.

In 2019, 7 years after my grandmother’s passing, I was encouraged by my partner at the time to work on these photographs. Having some emotional distance, I was able to discern that these images were genuine and had something powerful to them. They felt real and honest and even though I wasn’t comfortable sharing something that painful and believed that no one would care about my dead grandmother, I proceeded to create a dummy book. I didn’t publish it at the time but it set off my urge to explore my connection to my grandmother. A couple months later I travelled for the first time to the house where she was born. I discovered the youth of my grandmother, Nette, a strong independent woman vastly different from what I knew about her. I created a second dummy book with this work which was published, 2 years later by a French publishing house called punto e basta. 4 years later, I self-published Gramie the work that started it all.

Could you share how you approach the process of creating a book? Do you first envision what you want the book to look like as a physical object? Do you wait until the photography and scanning stages are complete before you begin editing the material? Or do you work on everything simultaneously?

There is no standard way. The photobook is something I’ve always loved; I even teach a course about the photobook at Stereosis Photography School. For me the most important thing is coherence. The object must be consistent with the project and vice versa. I sometimes think of the object in advance and sometimes it comes along the way. At some point I will visualize the book in my head as an object quite clearly. I usually know exactly what I want in accordance to the nature of my work.

The integration of photo-text has always been a challenging and intricate process in constructing a narrative. In Gramie, we observe photos harmoniously paired with drawings and accompanied by your grandmother’s words, creating a compelling synergy on the spreads. What motivates you to combine photos and drawings? Could you elaborate on a specific example of a spread from the book?

After my grandmother’s passing, I found out that my mother had kept one of her notebooks from school. It is one of the very few things she kept along with a couple of old photos. Inside that notebook I discovered multiple intricate drawings she did for her biology/zoology class. I was blown away by the detailed and skillful sketches as I had no knowledge of my grandmother drawing at all. It was around that time that I began entertaining the idea of creating a photobook and it made sense instinctively to incorporate these drawings as one of the only and last things I had from her along with the photographs I took back then. The connection was mainly visual, for example in the first spread where we see my grandmother playing with cards in her kitchen on the left page, there is a drawing of an insect resembling her hand on the right page. There is no particular semantics there, I wanted to integrate all these pieces I had and try to make sense of them.

You’ve mentioned that your exploration of your family archive was greatly aided by the fact that your father was “very much a record keeper.” Could you describe your father’s connection to photography and how that influenced your decision to pursue photography as both a field of study and a profession thereafter?

When I graduated from school, I was admitted to the university but started to take photography lessons in Stereosis Photography School at the same time. I fell in love with photography quite instantly and thus started to spent all of my time in the darkroom and reading photobooks. I wasn’t attending the university at all and was lying to my parents about studying there. This lasted a couple of months but wasn’t sustainable, I therefore gathered all my courage and confronted my parents telling them photography was the thing I wanted to pursue in life. As a child I always remember my dad taking pictures but I didn’t know he actually had the same talk with his father when he was 18, telling him he wanted to become a photographer. Of course, the 70s where considerably different and being a photographer wasn’t considered to be the ideal career for parents at that time (it still isn’t), so my grandfather laughed and said “now tell me a real job you want to do”. So, when I talked to my parents, my father told me that it struck a sensitive chord in his heart as he had been in the same position. It was quite touching and I was actually extremely lucky to have all the support from my parents in my decision.

The first photo in the book, following the title page, is captured from a low angle, reminiscent of a child’s perspective gazing up at a house. Does your work serve as an ode to those aspects of childhood that adults often long to preserve?

I never thought of that. The truth is that I’ve spent time in that house much more as a child than as an adult. Maybe that’s why when it came to photographing it, the child’s gaze emerged intuitively. I felt that things were coming to an end with my grandmother’s impending death so maybe I tried to preserve or to return to that kind of memory.

Do you intend to create a third book that references Genevieve Fenouil, thus completing a trilogy?

The trilogy has been completed with a dancefilm I created in October 2022 during my residency at Akropoditi Dance Center in Syros. It is called Nette – A kinesic experiment. Kinesics is the study of the way in which movement serves as a form of non-verbal communication. It was an attempt to record a kinetic improvisation in interaction with archival images of Nette (my grandmother) in motion. I wanted to explore the wider connection of image-movement and a different more experiental way to relate to my grandmother though my body. The creative process resulted in a short experiential dance film; a multisensory experience powered by my inner need for constant movement.

In addition to its printed version, your project has already been exhibited in two exhibitions. How do you adapt it for display on exhibition space walls? Do you tend to stick closely to the core of the book or do you prefer to experiment from scratch? Could you share documentation photos of your favourite setup?

The way I present this particular work has something elliptical and more abstract in its narration. It can therefore easily adapt to different spaces. I like to experiment and combine different materials and sizes. I think this kind of setup works in this project as the elements that compose it are like fragments that can be read in no particular order.

What are the possible dynamics between photography and dance?

When you actually think about it there might be no dynamics between those two, as photography is inherently a still image while dance is movement. However, for me as I have been closely interested by both for several years it became a challenge and an urge to find a way and combine them. And so, I did through my dancefilm Nette – A kinesic experiment which I mentioned earlier.

In addition to developing your own work, you have been a photography teacher for several years. Having attended one of your classes one day in the past, you seem to put a lot of energy into it. Why do you enjoy teaching?

I have been teaching for the past 11 years. It’s something I really enjoy because it gives me the opportunity to constantly expand my knowledge. I have the chance to be able to share things I’m passionate about but also interact with different people on these things and thus gain perspective. It is also rather important for me the fact that I teach in Stereosis Photography School, right where I started almost 20 years ago. This is where I first fell in love with photography and it means a lot to me to be a teacher there. I think I could do it forever.

Can you give us some info about how Photography is perceived as a medium of art in Greece? What do you appreciate the most?

I don’t think I can give a well-rounded evaluation of what Photography means in the art world in Greece today. I can only speak about my experience. Having lived in Paris, one the epicenters of photography in the world, for several years I appreciate the effort and authenticity of the small communities in Thessaloniki, trying to push things forward and share creative things in a more human scale.

What is the most significant contrast in your perception of art today, in comparison to your initial days at university or when you took your first shots?

When I started off, I always thought that my photography had to be “good“ (whatever that meant) and that it could only be pertinent if people liked. My perception has evolved a lot over the years. I believe that art has meaning only when it arises from a profound need and therefore it contains something inherently real.

More on her website